A momentous development quietly streamed across the news wires late Thursday night – only noticed by those who would listen, but a development that, nevertheless, will undoubtedly continue to transform the shifting political landscape of a younger and more vibrantly ambitious Central America.

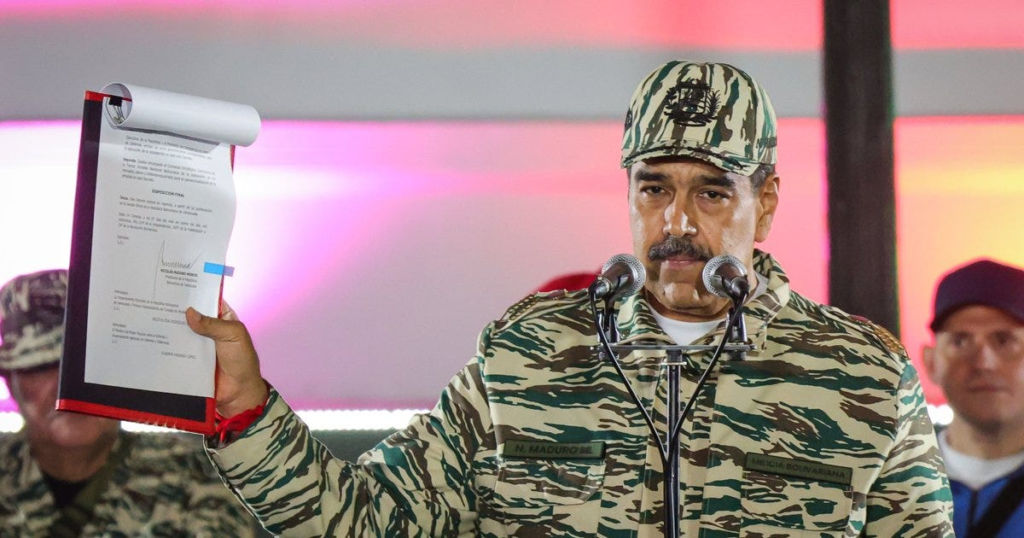

Already burdened with suspicions of treading down the gradual and slippery slope of an uncompromising authoritarian rule, the administration of President Nayib Bukele managed to couch the narrative quite differently, selling it as an exercise of the will of the people to elect the leader they wish to have themselves led by.

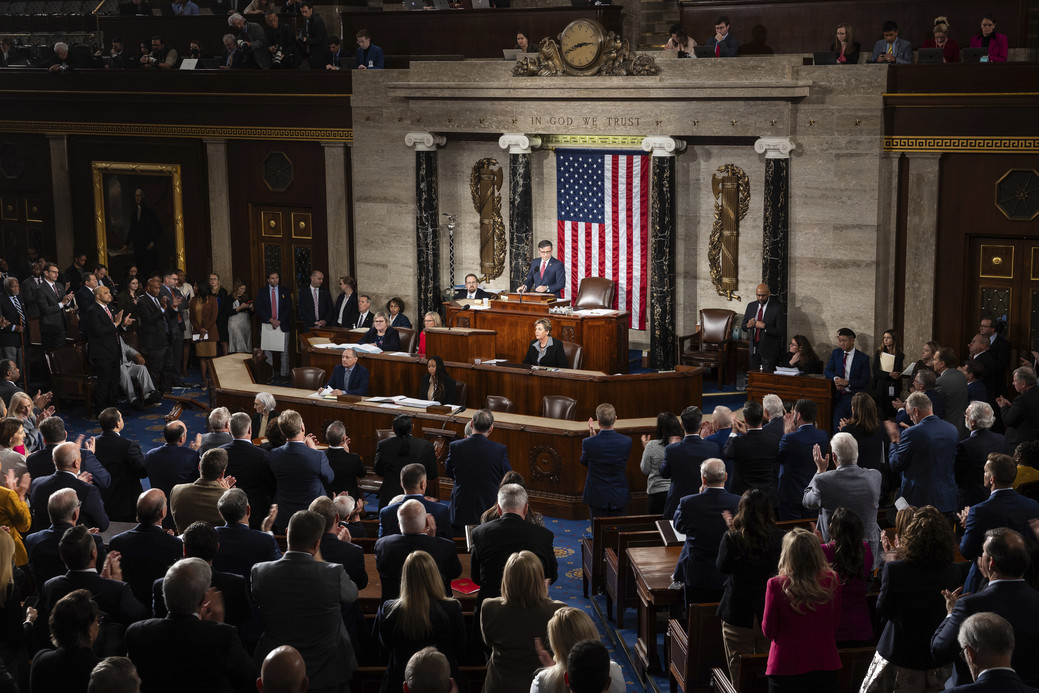

The development came after the nation’s legislative assembly approved a series of constitutional reforms that will further reopen these suspicions of a return to the way things were, once before in the region.

During the 1930s, a political trend in Central America came into being, and one that became synonymous with the strong-handed manners of government so commonly found in the nations of the Isthmus.

It was called continuismo, whereby a political leader, manifested through an image of personality, rather than policy, boasting a strong military background, who has risen to power on the waves of a populist nationalism, almost willed into power by the people with a mandate to restore their nation to its past greatness by building a no-nonsense internal security apparatus, governing his nation-state with a conservative mandate and an uncompromising demand for the rule of law (although, more often his law, than not).

This was the age of the caudillo, who was absurdly corrupt, and the length of their tenures always seemed to be extended by legal means, and never through coercion, until they were inevitably made regular and unchallenged.

The caudillio, who ruled by extension of an arbitrary police force, judicial acquiescence, and censorship, seemed to always have gotten what he wanted, and when he wanted it. The people, however, never did; for a caudillo is not a caudillo if his power and influence are not exerted at the expense of the people, and without compensation.

This is the man critics claim is Nayib Bukele, the 44-year-old current President of El Salvador with Palestinian heritage. Surely, they will continue to say it, especially after Thursday night’s ground-shaking measures when Bukele’s Nuevas Ideas (New Ideas) party, approved amendments to the nation’s constitution, allowing President Bukele to extend his already extended term, ending term limits to the office of president, and paving the way for indefinite presidential elections, if the president so chooses to pursue it.

Congresswoman Ana Figueroa, a prominent member of the Nuevas Ideas party and catalyst for the legislation proposed, brought forward several articles to amend the constitution. The reforms include:

- An extension of presidential terms from five years to six.

- Allow for indefinite presidential reelections.

- Eliminate the second round of elections, where the two top vote-getters from the first round face off.&

- To shorten the president’s current term by two years, to synchronize elections in 2027 to place presidential/legislative elections on the same scheduling cycle.

Bukele won the last presidential election in February of 2024 in a landslide victory, despite there being a constitutional ban that prohibited presidential reelections. Thursday night’s measures also absolved Bukele’s second term of any constitutional ambiguity, thereby validating his second term in the annals of Salvadoran presidential history.

The amendments passed in the legislative body in a 57-3 vote, where Bukele’s Nuevas Ideas party holds a supermajority.

Bukele is expected to win handily in the 2027 presidential election, but domestic opponents of his, like Marcela Villatoro of the Nationalist Republican Alliance party (ARENA), announced that “Democracy in El Salvador has died”, following Thursday night’s measures.

Bukele, labeled a dictator by many in the international community, bears the single highest approval rating in the entire Western hemisphere, a number backed up by impartial third-party organizations without affiliation to El Salvador. The overwhelming criticism of Bukele is that he is a strong-handed autocrat who acts without any regard for the rights and civil liberties of his civilians, alluding to his major crime crackdowns, allegedly bypassing legal procedural processes for individuals merely suspected of ties with the nation’s criminal underworld, and detaining untried individuals in El Salvador’s notorious Terrorism Detainment Center, CECOT.

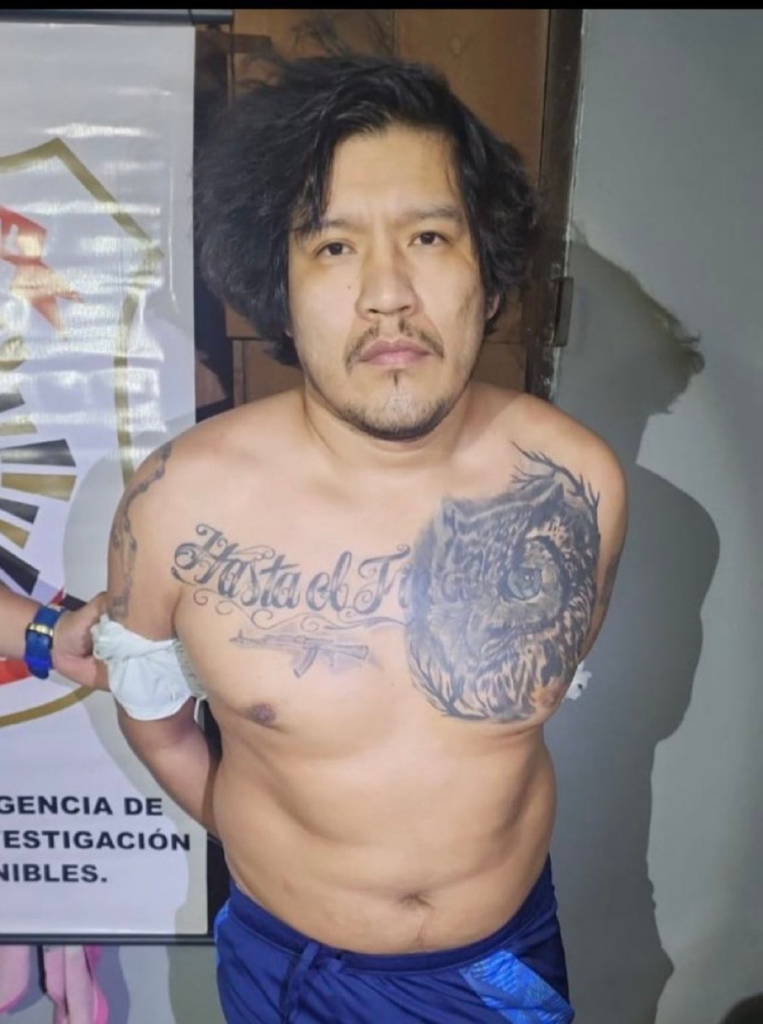

Since his ascendency, over 75,000 Salvadorans have been arrested and detained amid a ruthless crackdown on the criminal element that terrorized the streets of El Salvador for the past two decades. Violent criminal gangsters, or maras, from organizations like MS-13 and Barrio 18 committed robberies, extortion, drug trafficking, kidnapping, and murder without impunity, and often with the aid of previous governments that did not have the will, nor the resources to eradicate these violent criminals from the public realm.

The gangs pushed El Salvador over the threshold in 2015 when the small nation of only six million retained the highest murder rate in the entire world.

Much of Bukele’s approval from the people of El Salvador emanates from his restoration of order and public safety, two elements of life the Salvadoran people have been lacking for half a century since the start of a brutal civil war that lasted 15 years during the 1980’s, and then the rise of the maras that quickly emerged in its wake.

Bukele’s party assured critics that it is the duty of government to provide the people, what the people want, and condemned any accusations that Bukele’s administration aims to become a dictatorship. Bukele proponents pointed out that, in fact, many countries in Western Europe also do not have presidential term limits.

Exponents derided this claim as ridiculous, arguing that such governments have parliamentary powers to act as a check, reminding that in the case of El Salvador, the legislative assembly holds no oppositional power – all of the power is in the hands of Bukele.

Bukele ran into a sticking point during the U.S. Biden administration when it denounced the Salvadoran leader as “authoritarian.” U.S.-El Salvador relations have since warmed with the reelection of conservative President Donald Trump, who has taken a similar approach to crime within his own borders.

Time will only tell how El Salvador’s young leader will continue to govern. The constitutional amendments do not mandate an automatic reelection to the presidency, but only make the option available if Bukele elects to seek a third or fourth term.