Roraima, July 30, 2025 –“VENEZUELA IS DEAD!” A bereaved migrant declared as he hiked his way south past the entry point, poking into Pacaraima, Brazil. Everyone knows it, but you’ll only hear it from those who were able to get out.

The crossing is more frequently used nowadays, in Roraima state, in the Amazonian hinterlands, a gateway that’s become a corridor for fleeing Venezuelan migrants who’ve decided to abandon everything and make their way south.

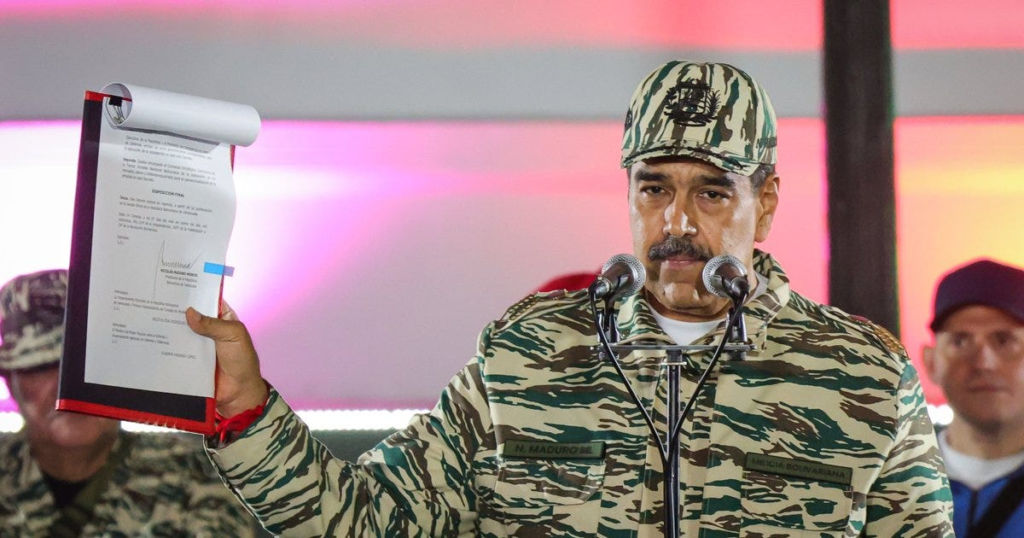

The brutal regime of Venezuelan strongman Nicolás Maduro is more isolated than ever, and when it suffers, so does the population.

Since the pandemic, over 500,000 of his own people have fled their homeland to seek refuge south across the Brazilian border. The small border town of Pacaraima has little to offer to its newcomers — fickle, temporary, make-shift migrant stations are set up to supplement these travelers for their onward journeys south. Some establish roots nearby, but most advance further into the jungle, where opportunities are more abundant.

However, as is so often the case in mass migrant crises, some of these surrounding areas across the border are beginning to feel overwhelmed. The massive influx of Latin American populations relocating south in Brazil has put tremendous strains on the small, nearby border towns and their residents, where localities do not possess the resources to satisfy the sudden growth in demand for even the most basic resources.

Brazil hosts a large number of Venezuelan migrants, and the numbers have been increasing since 2017. The Brazilian government has taken a different approach to mass migration compared to some of its neighboring countries, like Colombia, Ecuador, or Peru. Unlike most countries, whose migration corridors are more restrictive, Brazil has favored an “open-door policy” of sorts, receiving large volumes of fleeing citizens from Venezuela, maintaining these populations in temporary border stations, and then cooperating with state-run services and the private sector to distribute these populations throughout a vast network of jurisdictions and contracted employers who are willing to shelter these migrants and employ them right away.

The program is called Operação Acolhida, (Operation Welcome), where migrants are absorbed into the Brazilian state, provided international protective status, and redistributed to various regions for employment and then given an opportunity to provide for themselves while also contributing to the local economies.

Latinoamérica21, a news outlet that focuses on events in Latin America, wrote an opinion piece on the Brazilian response to the Venezuelan migrant crisis in January, commending its success, and encouraged other nations in the region to adopt a similar approach. The best policy, of course, is to have no migrant crises. However, if one is necessary, and the exodus is so obscene to such a degree that foreign governments are unable to sit idly by and become spectators to the affliction wrought by the Maduro regime, a policy such as this one would be most favorable in equally distributing the responsibilities throughout various jurisdictions.

The carnage, chaos, and destruction witnessed during the U.S. Biden administration in its management of the migrant crisis along its southern border will not, perhaps, be outshined by a more befitting example in our lifetime.

If a government must carry out a responsible migrant response policy, it would help enormously if the local jurisdictions — which are so overburdened to intake such large quantities of people — be speedily alleviated of their share by the equal and expeditious distribution of these migrants to jurisdictions more aptly suited to provide for these populations.

In President Biden’s case, this did not happen (not to mention that the conception of adequately assimilating roughly 15 million people in four years is a ridiculously impossible feat). But as 21 noted in its piece, “like most refugee-hosting areas, the communities least able to respond and assist migrants are often the ones receiving the highest numbers.”

The Brazilian border state of Roraima, in which these Venezuelan caravans settle for some time before they resume their journeys south, has been inundated since 2017, and the “open-door policy” is not without its drawbacks.

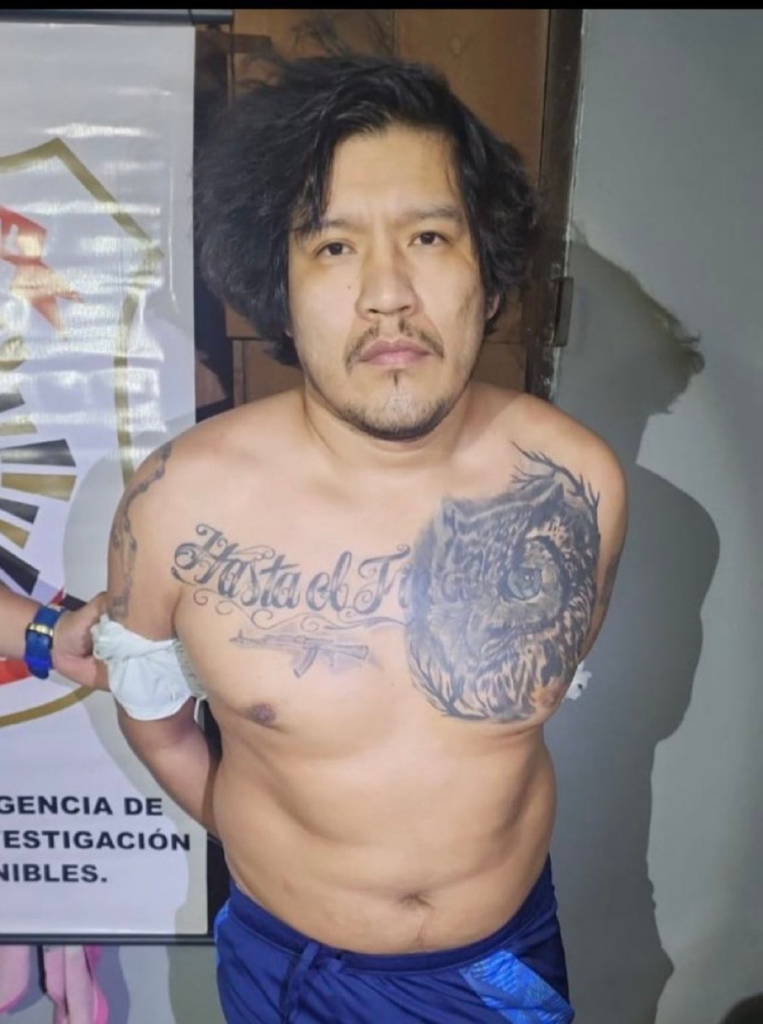

Last month, in June, Folha de S. Paulo, a popular Brazilian news outlet, published an article about the capture of a 34-year-old Venezuelan national who was wanted in connection to the murder of another 16-year-old Venezuelan minor in the capital city of Boa Vista, in Roraima state.

Boa Vista, a city of roughly 300,000 residents, has become an enclave in recent years for Venezuelan migrants looking to start anew in the Brazilian border region, where opportunities for employment have proved to be more numerous. However, precisely because of this presence of a large and vulnerable population of people who have no connections to the land, the community, or the local people, many often become ensnared in nefarious activities to generate income, many others gravitate to predatory gangs who prey on the young and unwitting, while others simply go missing.

The young 16-year-old Venezuelan victim, whose identity was not named because he is a minor, had been previously housed in a migrant camp in Boa Vista under Operação Acolhida, or Operation Welcome. The suspect, 34-year-old Andrés Marcelo Mendez Perez, is believed to have links with the notorious Venezuelan street gang Tren de Aragua. Stories like these are numerous and have become more frequent since the start of Operation Welcome.

Brazilian authorities also have evidence that the Venezuelan gang is involved in various criminal activities, including drug trafficking, prostitution, and murder in Boa Vista, and is also believed to be coordinating with two of Brazil’s largest criminal organizations: the PCC (Primeiro Comando da Capital) and the Comando Vermelho in the remote Amazonian region.

In 2018, the Brazilian Armed Forces deployed personnel to the region after a Guyanese territorial dispute with Venezuela, after the Venezuelan government hinted at a potential land grab of the oil-rich nation. Military personnel have since maintained a presence in the region in an effort to retain order following a tumultuous period of gang violence.

In 2021, there was a wave of assassinations in the Boa Vista region that counted Roraima as the fifth highest state in homicides, with a rate of 35 per 100,000 by the end of that same year. The vast majority of these victims all had one thing in common — they were Venezuelan, and according to the Civil Police, their murders were carried out by Tren de Aragua.

According to InSight Crime, a data & research group focusing on organized crime in the region, reported:

“In 2018, Roraima registered the highest number of violent deaths per 100,000 inhabitants in the country, 54% higher compared to the previous year. This led the federal government to sign an agreement with the state government of Roraima to create an Integrated Force to Tackle Organized Crime (Força Integrada de Combate ao Crime Organizado) in 2019. According to the Federal Police, the increase in homicides was caused by the First Capital Command (Primeiro Comando da Capital – PCC), a criminal organization that emerged in São Paulo and has a broad presence in Amazonian states today.”

Today, Venezuelan migrants continue to arrive in Roraima state, and due to the relentlessly deteriorating economic and sociopolitical situation in Venezuela, there is a real likelihood that the trend will persist. The crime rate in Roraima has since reduced as Brazilian authorities continue to crack down on organized crime in the region, along with serious attempts to shut down their various operations in the region that have gradually transitioned into other covert means like illegal mining operations deeper into the Amazon regions.

Here, too, many unwitting migrants fall into the snare of organized crime, and yet, many others are also willing to participate in it.