Since the start of the Sandinista revolution in ‘79, Nicaragua has learned to master a carefully played game of statesmanship whereby the country would maneuver to retain its own politically socialist sovereignty, whilst at the same time learn to make strategic concessions to Washington in order to get along on more friendly terms with its more powerful northern neighbor.

Daniel Ortega, the country’s long-time dictator and founding revolutionary member of the nation’s ruling FSLN party, has differed much from Fidel Castro, and how he’s managed to captain his country beneath a backdrop of unceasing U.S. pressure to open Nicaragua’s political process to democratic reform and free enterprise.

Although Castro was the source of much private counsel for Ortega on how to ward off U.S. intervention during the bloody years of the Nicaraguan Civil War of the 1980s, Ortega was less the renegade zealot that Fidel was, nor did he become as totally uncompromising in international affairs as his Cuban counterpart, or as wildly intractable and willing to plunge his own people into the depths of a Cubanesque misery and despair just to thumb his nose at the domineering North Americans.

The rule of the Ortega dictatorship, although violent and repressive, and quick to exact retribution or political reprisal against civil society organizations critical of his government, or opposing political figures whom he has judged as threats to his own personal power, Ortega was more pragmatic than the more fervent figures of Latin American socialism, instead opting to align his country’s trade policy with the United States in an effort to formulate his own model of an at least inhabitable Latin American socialist state.

The Americans to the north, once a bitter enemy who had their hands in a vicious civil war that claimed the lives of roughly 80,000 Nicaraguans after the rise of the Sandinistas, is now the largest trading partner of the Central American republic. The United States takes up about two-thirds of Nicaraguan exports and is Nicaragua’s largest source for crude and refined petroleum, unlike the Cubans, who have historically turned to the Russians, and later Hugo Chavez in Venezuela.

The United States is also its largest trading partner in imports. The recently announced increase on tariffs during the second Trump administration are feared to have a jarring effect on trade policy among the Central American republics, however, those tariffs were ultimately reduced from the original 19% increase for Nicaragua in April, down to a modest 10% across all Nicaraguan imports as part of President Trump’s 90-day pause.

Politically, allegations lobbed against the Nicaraguan government have mounted for years. The United States, human rights organizations, and other Western governments have accused the Ortega government of undermining democracy by violating civil liberties, running a vengeful surveillance state, and closing off the nation’s democratic process that once offered the Nicaraguan people alternative party representation.

Ortega’s government is also accused of seizures of private property, the detainment of political prisoners, the expulsion of local journalists and a vicious crackdown on national protests that took place in April of 2018, during which thousands of Nicaraguans took to the streets of the nation’s capital of Managua to clash with state security forces to protest increased taxes and reform measures made to the nation’s pension system – a system on which many Nicaraguans rely for subsistence.

Ortega then unleashed las turbas, or the mobs (an armed para-police organization operating with the full backing of the Ortega regime) as a response in order to suppress the populist unrest, resulting in the killings of over 300 civilians over the course of the demonstrations.

In October of 2020, Nicaragua’s National Assembly approved legislation called Ley de Regulación de Agentes Extranjeros, or The Law for the Regulation of Foreign Agents, which requires any nonprofit organization that receives foreign funding whilst operating in the country to register with the Nicaraguan government.

The law essentially gave the ruling government party – the FSLN (Sandinista National Liberation Front) – complete oversight over how and on what “projects” nongovernmental foreign aid should be spent. Funding for “projects” deemed contrary to the national (party) interests would therefore be funds not permitted and subject to arbitrary fines, sanctions, or seizures.

The legislation received tremendous backlash from not only the more developed nations of the United States and members of the European Union, but it also took heavy criticism from the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, the paramount arm of the Organization of American States (OAS) dedicated to the protection of human rights and civil liberties in the Western Hemisphere.

Relations between Nicaragua and its American neighbors have been tenuous at best, marred by a mutual contention between the U.S. struggle to pressure the Ortega regime to implement measures to help bolster democracy and free elections, and on the other hand, the calculating arrangement orchestrated by Ortega to balance more cordial trade relations with the United States that help serve his nation’s interests.

But for years Daniel Ortega has sought to build closer ties with the likes of Venezuela, Cuba, China, Iran, Russia, and North Korea to counteract any further political pressure from the West, especially since reassuming the Nicaraguan presidency in 2006 after a brief ouster from power in a rare and not since repeated election in 1990. Critics have claimed Ortega’s reelection in 2006 as a fraudulent reclaim to power.

Nicaragua is today one of the poorest nations in the hemisphere, with an economy still heavily oriented on agriculture, and dependence on remittances, mostly from the United States, increasing in recent years to equate to roughly one-fifth of the country’s GDP. Unemployment reached more than 60% during the second half of 2023, with about 40% of its residents living in poverty.

Increased migration of Nicaraguans north during the U.S. Biden administration and its effect on the return of capital to help serve families who’ve stayed behind have helped buoy Nicaragua’s economy coming out of the hardships of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Investments in an expanding services, hospitality, and tourism sector have also helped to stimulate Nicaragua’s economic growth, which rose approximately 4.6% in 2023, according to World Bank Group.

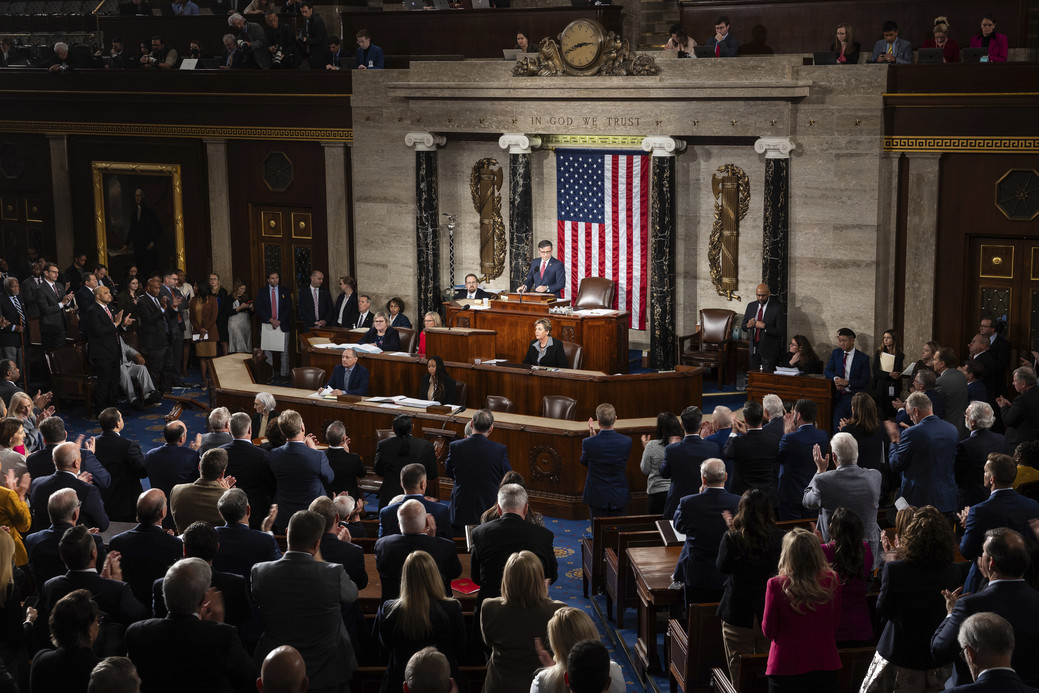

This careful balance is not something new to Ortega and the Nicaraguan government. It is a balance that has been worked on for decades. During the latter years of the U.S. Carter administration and for much of Ronald Reagan’s presidency, Ortega and his close allies of Sandinista revolutionaries during the early years of their power have gained some ground from a delicate process of siphoning financial and economic aid from the U.S. government. At the same time, taking advantage of the internal divisions of U.S. domestic politics and the halls of Congress on Capitol Hill in an effort to frustrate U.S. intervention during the difficult years of the civil war, and to further disrupt U.S. influence in the decades thereafter.

In November of 2018, following the violent crackdown on protests that same year, President Trump imposed a slew of sanctions by executive order upon Daniel Ortega’s wife and then Vice President, Rosario Murillo, and two other top officials, accusing them of undermining democracy.

Relations between the Nicaraguan and U.S. government have since been largely cold and indifferent. Dozens of other sanctions have been imposed on other officials of the Nicaraguan government, but beyond this, affairs are quiet and stalled in no-man’s land.

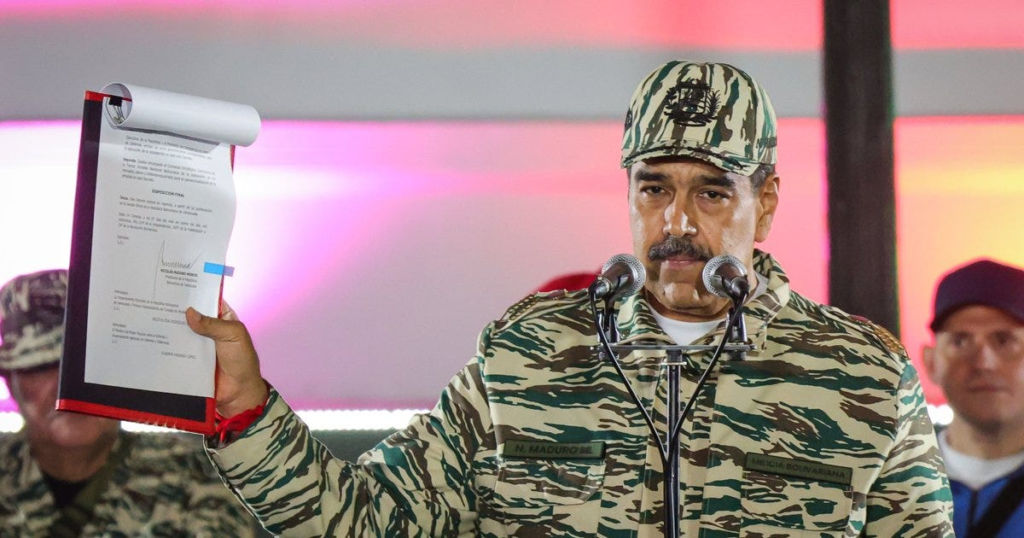

It wasn’t until early May of 2025 that waters were again unsettled when Ortega held a rally during International Workers Day in Managua and was overcome by a tirade.

In a speech lasting nearly 40 minutes, Ortega railed against the new Trump administration, criticizing his “anti-immigration policy”, trade tariffs. and expansionist ambitions reminiscent of early 20th-century U.S. interventions in Central America.

The onslaught came shortly after the Secretary of State Marco Rubio’s U.S. State Department released a First 100 Days Fact Sheet that ultimately labeled the Nicaraguan government of Ortega-Murillo as “adversaries” for “depriving the Nicaraguan people of their fundamental freedoms and forcing many into exile.”

For the past several months, Ortega had been reluctantly, but at least willingly accepting return flights of illegal Nicaraguan migrants residing in the United States back to Managua as part of President Trump’s scorched-earth deportation campaign. This agreement has made the U.S. president’s immigration enforcement policy less difficult. However, it didn’t take long for fissures to reemerge.

It has become clear that over the years, the positive flashpoints that have arisen from U.S.-Nicaraguan relations are resoundingly based on trade. As improvements to the private economic situation for the masses of Nicaraguan residents may be concerned, any benefits that have the highest potential to be accrued will continue to depend on such an arrangement of economic interests between the Ortega-Murillo regime, partners in the region, and opportunities where the Nicaraguan government and the Unites States see agreement on areas of mutual advancement.

On the political front, however, the prospects for progress are much more dim, and blighted by the old habits of their history.