The aerial views capture the story beneath the pock-marked surface of the wounded sections of the Amazon, penetrated by the greedy lust for precious metal. The same chase for gold that tormented the Spanish Conquistadores and the colonial rule that followed suit, now entice thousands of cadres of illegal mining operations that set up shop, literally carving out pieces of territory deep within the forested terrain in search of golden deity.

The price of gold was trading at $3,284 by 9:05 AM Eastern time Monday morning, representing a 30% increase from its price a year ago. The going rate for a little more than a gram of the precious metal runs about $60 USD in the global economy – a fortune for a poor, illegal gold miner in the pits of the Amazon forest.

Today, dozens of major multi-national enterprises deploy millions of dollars worth of the newest technology and heavy machinery operated by hundreds of technicians with foreign passports who answer to irritable shareholders in London and New York City. These companies are provided concessions for their work and pay a fee to the host government to operate these mines with permission from Brazilian authorities.

However, the gold rush is also attracting groups of illegal mining operations called garimpeiros that take advantage of the vast expanse of the Amazon rainforest, hauling in their jimmy rigs deep into the vegetation underneath the canopies of the Brazilian jungle and out of sight from Brazilian authorities like IBAMA (Brazilian Institute for the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources), who are dedicated to monitoring and enforcing illegal mining regulations in the Amazon.

Illegal operations have been on the rise in recent years due to the influence of criminal drug organizations and violent cartels that are becoming increasingly involved in the trade as a means of funding some of their other illicit operations. Armed invaders who work in groups will often seize and occupy territory inhabited by Indigenous tribes who do not possess the weaponry to defend themselves from the incursions.

In June 2020, two members of the Yanomami tribe – the largest isolated tribe in Brazil – were killed in the Serra de Parima region along the Venezuelan border when the two tribesmen approached a miner’s camp to reportedly ask for food. The murders are still under investigation by Brazilian authorities.

Illegal gold mining is an enticing venture for these criminal organizations because of the ease by which the proceeds can then be laundered. Human trafficking and the use of desperate and unrepresented migrants from other parts of the region exacerbate an already complex and multi-faceted criminal industry that is closely linked with other methods of criminality exercised by cartel organizations.

The Brazilian government has made minimal effort in combating this trend, bolstering law enforcement resources to patrol the terrain and cutting off the supply networks for existing mining operations in lucrative Yanomami lands.

After the election of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, the President of Brazil, affectionately known as “Lula” campaigned on prioritizing the eradication of illegal mining in Brazil’s Amazon.

Several initiatives were proposed such as limiting flights or river transports in the area that frequently provide illegal miners with supplies or attempting to block off any access to areas not authorized by authorities. However, none of these initiatives were ever enforced, including a no-fly zone that was meant to reduce the air traffic of unregistered flights that undoubtedly supply illegal mining operations with equipment and other material used by these illicit groups, according to the Center of Strategic & International Studies.

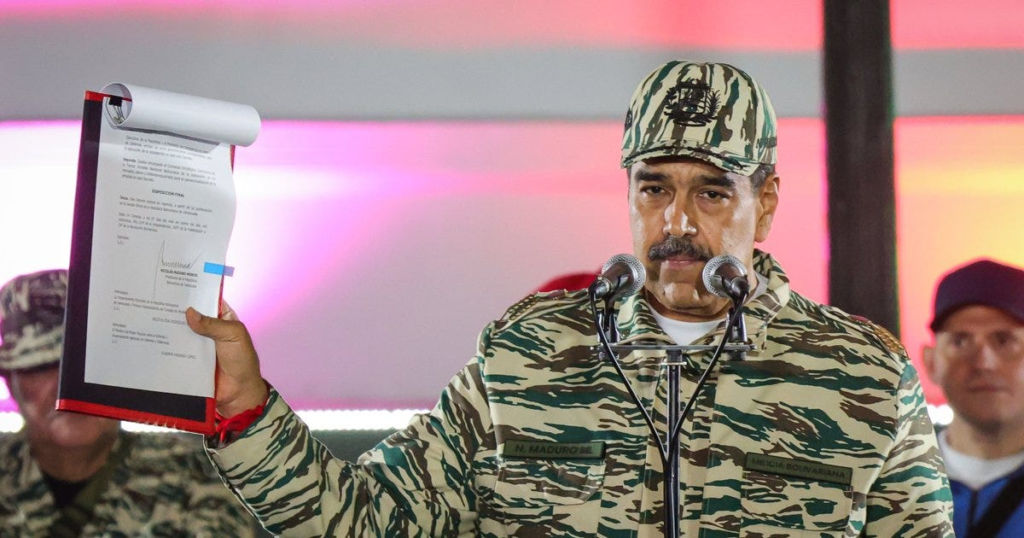

Alternatively, other governments like that in Venezuela – which has large portions of its own national territory within the Amazon rainforest, are arguably complicit in the illicit trade, evidently encouraging non-state criminal organizations to exercise illegal mining operations in Venezuela’s forests to generate revenue for the now defunct state that has lost any capacity in enforcing its own laws .

Ecuador on the other hand, another South American country that shares its territory with the Amazon has allocated resources to help repel the growing threat of illegal mining operations. Ecuador’s government has also dedicated a great deal of effort through scientific studies to determine the environmental impacts these mining practices have on the ecological health of the surrounding area, its wildlife, and the harm these operations are inflicting on the native Indigenous populations that inhabit the terrain, as well as the crucial food and water sources these populations rely upon to survive and sustain their communities.

Mining for gold was always a difficult business. If fortune were generous, trackless environments located in often unforgiving terrain would be accommodating enough to allow miners to find their way through the rough vegetation, striking gold before expenses and supplies would run out.

Finding the gold is an almost impossible feat, identifying a tiny piece of rock the size of a gram not only in the vast expanse of undeveloped forestry but also deep enough to where thousands of pounds of heavy equipment need to be hauled in to access it.

Mercury has been used to pull gold since Roman times, even earlier than that. Mercury is inexpensive and easy to transport. The mercury is used to recover these small pieces of gold, acting as a “gold magnet” that chemically binds to gold dust mixed in with the soil and sediments underneath the surface of the earth. The two compounds then settle together, creating an amalgam that is then vaporized, thus burning off the mercury leaving only the gold as a final product.

This process has created tremendous pollution and contamination that harms the local Indigenous communities and native wildlife of the Amazon’s ecosystem.

The use of the amalgamation process to mine for gold has been prohibited by the more developed nations since the 1960s because of the negative health impacts on local ecosystems. However, the proliferation of small-scale illegal mining operations in South America is a situation in crisis, where local governments simply cannot sustain the capacity to enforce anti-(illegal) mining regulations in the Amazon as the widespread use of mercury is degrading the natural environment to catastrophic consequences.

More recently, Ecuador ratified an agreement from the Minamata Convention in 2016 that controls the use of mercury in countries that experience systemic abuse from small-scale illicit mining operations. In 2022, a scientific research study funded by the European Commission for mining industries found that in the Northern Ecuadorian Amazon, 90% of artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM) used mercury in their operations, with ASGM being the largest source of mercury pollution on earth.

In another study, it is estimated that in Latin America an average of 4.63 grams of mercury is produced and lost in the Amazonian rainforest for each single gram of gold extracted.

In a separate report by the Ecuadorian Ministry of Environment, found that “29.6 tons (29,600 kg) of mercury were released into the environment through losses per year.” According to Amazon Frontlines, an environmental impact group that promotes Amazonian conservation equates this scale of contamination to being enough to contaminate 29.6 million 20-acre lakes.

Indigenous Amazonian lands hurt the most are those with copious amounts of gold deposits recently discovered by renegade miners. The Napo and Pastaza in Ecuador including the Aguarico, Cuyabeno, and Bobonaza rivers were discovered to have patterns of “heavy accumulation in fish” and other wildlife food sources for the hundreds of Indigenous communities that depend on these local ecosystems, Amazon Frontlines noted.

In Colombia, the southern department of Putumayo has native communities that reported exorbitantly high levels of contamination from amalgamation in the Colombian Amazon.

Pregnant women are the most vulnerable to mercury contamination, known to produce adverse health effects for pre-born children. Birth defects, deformities, and diminished child IQ levels are common in communities in such proximity to areas with extremely high levels of metal toxicity.

In Brazil, Munduruku Indigenous territories, deep within the Amazon Rainforest are hit hardest by the garimpeiros. Increasing attacks from armed groups of miners who are waging a war of terror against the community.

In 2020, Brazils’s Supreme Court urged the government to take stronger action against illegal miners, however, such steps have yet to be taken. Vulnerable community leaders and tribesmen from the area also fear increasing threats from invaders who are expanding their footprint and introducing additional mining machinery on Munduruku lands.

Indigenous fears are not only of armed men who terrorize their communities but also the proliferation of metal toxicity and the spread of diseases that illicit miners bring with them.

To make matters worse, Brazilian authorities are now learning that Indigenous participation in illegal mining throughout the territories is also becoming more common as native groups are confronted with food and water insecurity and ineffective government assistance.

The Brazilian government is now formulating development projects and alternative income programs to enhance Indigenous sustainability in an effort to discourage Indigenous tribes from resorting to illegal mining practices that are becoming more pervasive in the Amazon.

The Brazilian government last week will be attempting by another tact to stunt the proliferation of illegal mining by partnering with space mogul Elon Musk.

Last week, in collaboration with Musk’s high-speed satellite service known as Starlink, the satellite arm of SpaceX, Brazilian authorities plan to curb the networking capabilities that illegal mining groups use to communicate with one another and coordinate their operations deep within the Amazon. The government wants to disrupt these communications adopted by criminal organizations.

The service will begin requiring identification features and proof of residence for all new users in the region starting in January. The company will also provide Brazilian authorities with “user registration and geolocation data for internet units located in areas under investigation”, according to the AP.

In order to tackle these environmental threats, more action from state and local governments in South America needs to be taken. Closer coordination between federal agencies and local Indigenous populations is required to have any meaningful impact in preserving the natural Amazonian resources in Brazil, Ecuador, Colombia, and Venezuela. However, such cooperation is often futile and even non-existent when the political will for these measures are unavailable.

Additionally, attempting to effectively coordinate with dozens (or even hundreds) of Indigenous communities located in the seclusion of the Amazon is almost insurmountable, especially when federal and local governments are not even welcomed by these Indigenous non-state entities.