The primary function of any legitimate government is to ensure the security and public safety of its own citizens. In a press conference held on Monday, the 2nd of June, 2025, the President of the Republic of Guatemala acknowledged the duties of government to be such.

But since taking office in August of 2023 after a surprise election victory over an entrenched political elite perceived by the public as a politically corrupt establishment, Bernardo Arevalo has appeared to fall short of serving Guatemala’s most basic function.

In 2022, a year prior to Arevalo’s election, Guatemala ranked among the lowest quartiles in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index of 180 other nations around the world. Today, three years later, without any marked difference, Guatemala is ranked 146th.

The son of former President Juan José Arévalo – a major figure of 20th century Guatemalan politics and one of the first caudillos of the Central American republics during the 1930s and 1940s – Bernardo, the former diplomat and writer rose to political prominence after forming one of Guatemala’s newest political parties called Movimiento Semilla, or Seed Movement in 2017, a center-left progressive platform established as a political alternative to the establishment right-wing political alliances of a privileged elite destined to tip the scales in Guatemalan politics for decades.

Arevalo’s campaign focused heavily on the issues of state corruption and internal security, trends that have been demoralizing for Guatemala’s residents, leading Arevalo over the edge in an upset landslide over his opponent.

Guatemala is situated geographically at the center of a bottleneck of major transnational drug routes seeping into southern Mexico, bridging distributors from the southern coca farms in Peru and Colombia to canopied production plants operating in the forested regions of northern Honduras, and facilitating the traffic of products north through Guatemala into southern Mexico, bound for the United States southern border.

Guatemala is one of the key transit areas for the illicit flow of narcotics in the entire region, attracting interest from criminal drug organizations and the violent crime that accompanies them.

Rampant crime in Guatemala originally gained a foothold following the Peace Accords that ended the civil war in 1996 between the Guatemalan government, backed by the U.S., and the Guatemalan National Revolutionary Unit (URNG), a far-left guerrilla organization that led a major insurgency against state security forces.

The peace settlement led to the complete overhaul of the nation’s military structure, which was further disintegrated as a result of the cessation of foreign aid from the United States when its involvement in the civil war had ended.

What was left in the power vacuum in the absence of any significant presence of any meaningful state security apparatus was the alliance of several local “familias”, or clans, who controlled the nation’s drug trade as the flow of cocaine produced from the Colombian highlands was being routed north into the Isthmus.

The political environment during these years after the bloodshed of the Guatemalan Civil War was mostly tame, however absorbed in widespread corruption as politicians profited from the pernicious drug trade. At the same time, violence and crime were mainly controllable and of relatively low levels.

During the late 1990s and early 2000s, the Mexican cartels, like the Sinaloa, began to move into northern Guatemala as they eyed an opportunity to get in on the action. Violence surged until the Mexicans were eventually pushed out by Guatemalan paramilitary units and local drug clans who sought to preserve profits from the trade for themselves.

However, Guatemala’s public safety was still lacking, state security forces were nonexistent, the nation’s military had been dissolved, and a national police force was totally ineffective in preserving the peace for its inhabitants. Crime spread vociferously, smaller gangs vied for territory, drug trafficking became fractionalized, robberies were rampant, and extortions from 2013-2021 reportedly doubled.

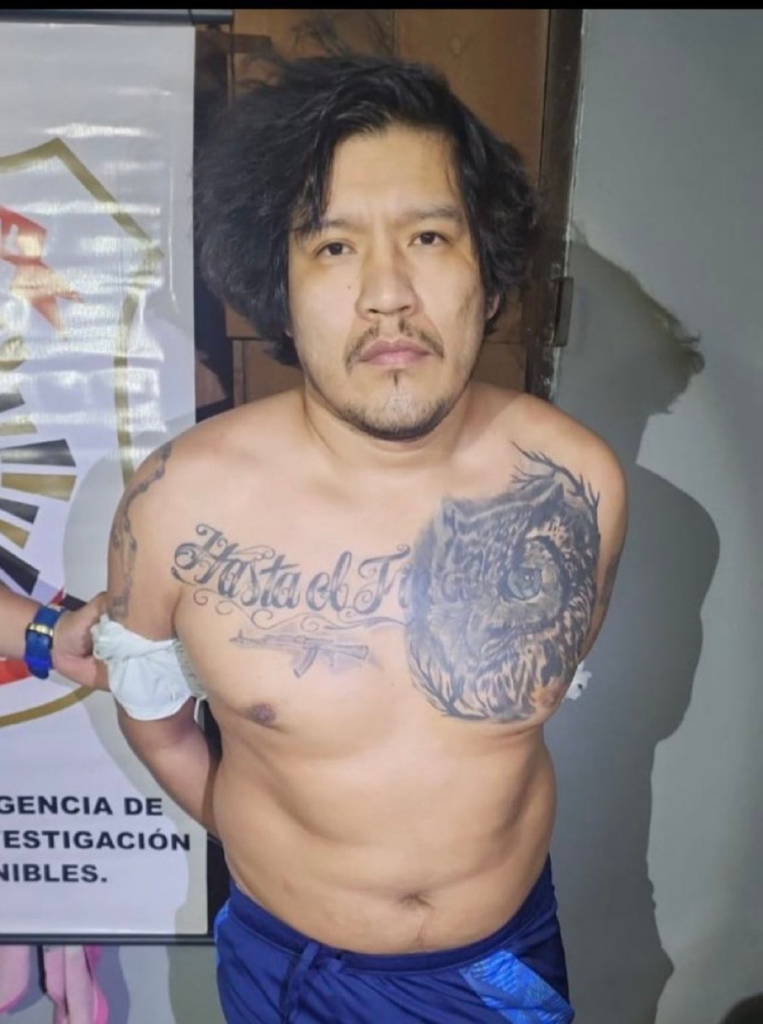

In 2016, gangs like the Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13) and Barrio 18 had carved out pieces of territory along the “outskirts of Guatemala City in the neighborhoods of Villanueva and Mixto”, according to a report that was written by the Steven J. Green School of International & Public Affairs. The city of Quetzaltenango in the western portion of the country is to this day a stronghold for criminal gangs operating in the city.

These same gangs have also established cells in neighboring Honduras and El Salvador, transforming the latter into the murder capital of the world in 2015. In Guatemala, “homicides had fallen from 46 murders per 100,000 in 2016, but remained one of the highest murder rates in the Western Hemisphere.

Only a couple of years into the reign of Salvadoran strongman, President Nayib Bukele began to drop a hammer on these criminal outfits by declaring a state of emergency and utilizing extrajudicial powers of his national police force with operational support from the nation’s military. The crackdown (with a state of emergency still in effect today) eradicated the streets of this criminal element, designating members and suspected members as domestic terrorists. This crackdown had broader regional implications as criminal organizations began to splinter with factions setting up shop in neighboring Honduras and Guatemala, submerged into hiding, shutting down operations, and were eventually made dormant.

Crime in Guatemala, for instance, grew less organized and more individual, but spread like wildfire as space was freed up for more localized criminal groups to take advantage of their newfound liberty. Eventually, crime spread not only throughout the outskirts of Guatemala’s major cities but also seeped into the cities, penetrating the posh-like tourist zones of the lower capital of Guatemala City.

A second and equally pervasive trend plaguing the Republic of Guatemala and its Central American neighbors has been the issue of persistent and unfettered mass migration.

Guatemala has historically been a transit country for the flow of illegal migrants transgressing the Isthmus from South America. Colombians and Brazilians come up through the treacherous Darién Gap through Panama, who wish to escape poverty and the stranglehold of the threats of criminal violence and gang retribution in their own countries.

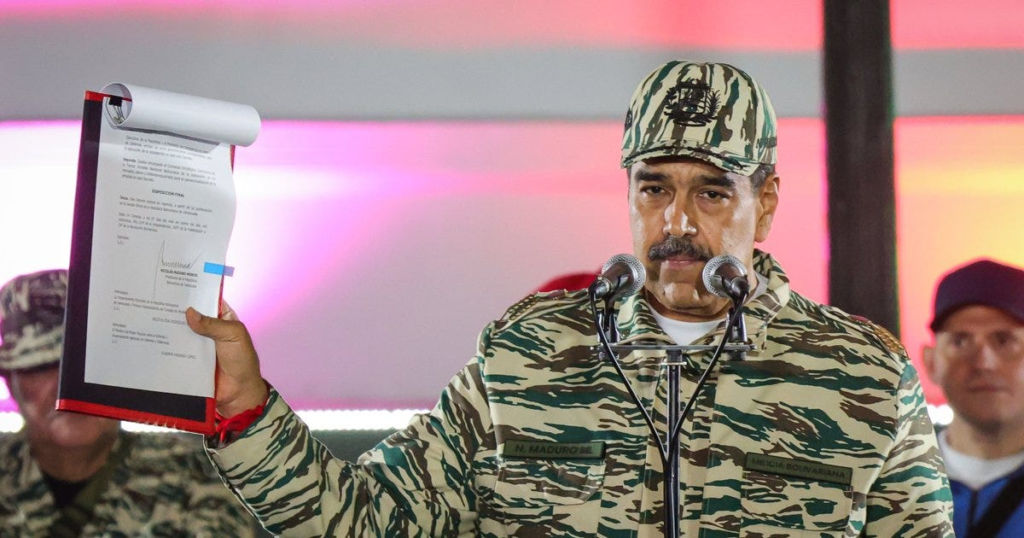

Venezuelans have recently made up the bulk of these migrant waves moving into Central America to make their journeys north. Many are fleeing the repression, political persecution, and economic turmoil wrought by the authoritarian Maduro regime. Many others have reportedly brought with them a version of their own criminal elements, for instance, Tren de Aragua.

Prensa Libre, a Guatemalan daily news platform has previously reported on the presence of members who may be associated with the Venezuelan organization, and remarked that these members have been suspected to be responsible for various crimes committed throughout the territory in Guatemala. However, according to Interior Minister Francisco Jiménez, “there is no evidence that the Aragua Train has an operational presence in Guatemala.” But the Minister adds that the more concerning problem is those who remain in the country as a result of immigration policies implemented by the U.S. and “become stranded”, and without recourse, instead resorting to criminal activity to provide themselves a living.

As a major transit country for the illegal flow of drugs and undocumented migration, it is typical for these two worlds – the migrant and the crime – in many cases to come to meeting, wreaking havoc on the local populace, draining public resources and absorbing the attention of a now bolstered law enforcement structure rebuilt since the end of the bloody civil war.

In his press conference on Monday, President Arevalo referenced the nation’s concerning increase in violent crime and “a rebound in homicide.” Arevalo urged his administration to “recognize it with absolute seriousness and responsibility.”

As part of its principal function of government, Arevalo recognized that “security is a national priority of the whole of Guatemalan society, it is the only priority of the government, and that is why we are taking concrete steps to… counteract this scourge.”

Arevalo in Monday’s presser outlined a fundamental restructuring of his top cabinet of the Ministry of the Interior (MINGOB), assigning Minister Francisco Jiménez with oversight over the “operational strategy” responsible for the reduction of Guatemala’s violent crime and increased murder rate.