Many say that this had been brewing for several years now, but the capital of Mexico City has been a haven for travelers and foreign tourists for years. The placid streets of the capital’s most tranquil neighborhoods, heavily shaded by the city’s trademark scenery of large jacaranda trees and the native ahuehuete that canopy the colonial sidewalks, and hover over pedestrians.

Young Mexican residents of the city have complained for years of being priced out of their own homes, pushed away by Canadians and affluent, remotely employed U.S. nationals attracted by the reduced cost of living and old Spanish culture.

Most residents attribute the cause to the current President of Mexico, Claudia Sheinbaum, who, as mayor of Mexico City in 2022, signed an agreement with short-term housing agencies like Airbnb to expand services throughout the city to help boost tourism.

The influx can also be attributed to the COVID-era when foreigners, mostly Americans, found a great deal of solace in some areas of Latin America that offered North American expats a higher quality of living without the exorbitant costs that are so typical of large U.S. metropolitan cities and suburbs. The push to broaden remote work to counteract the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic catapulted many people who had professions that could accommodate working from home to relocate then and find refuge in places south of the U.S.-Mexico border, including Colombia, Ecuador, Costa Rica, El Salvador, and Mexico.

The transformation of Mexico City since then has been noticeable, as small corner stores where residents used to shop for their daily groceries have been replaced by higher-end vendors like cafe bars, wine stores, and refined restaurants. Young, native students who attend university in the capital area used to frequent these local stores for subsistence, but have since been pushed out due to the affordability impact of the foreign influx and growth in population.

The city’s housing supply is also now limited because of the influx of people relocating to central Cuidad, which has the effect of inflating rental costs for local residents. The city’s favorable tax system for foreigners interested in resettling in Mexico City has disenfranchised the native population, further exacerbating tensions as Mexicans residing in the nation’s capital feel that they are being treated unfairly or as second-class citizens in their own country.

The issue of gentrification – or gentrificación in Spanish – is a hot topic in Mexico, especially in the capital of Mexico City, which understandably has the highest ratio of foreign-born to native-Mexican population in the country. It’s a hotly contested and extremely divisive issue, partly because at times it can revolve around not only racial implications, but also disparities in class representation, too.

Latin American governments – governments to be precise can typically be less accommodating to the concerns and the interests of their lower-income native citizenry of their countries. If there are opportunities that are presented in these countries, whereby governments can onshore more investments in their development sectors, stimulating tourism industries and welcoming people from abroad, and from more developed countries to spend money or relocate to the region will often relegate the interests of the native population that would inevitably be supplanted by the new revenue streams generated from planned developmental projects, residential expansion, or large commercial sites.

This has occurred on a smaller scale in Mexico City and within smaller localities of the capital albeit, however, the lives of many native residents have arguably been disrupted, if not, totally uprooted due to the socio-demographic transformation the city has undergone for several years, and the government in Mexico has received much of the blame for this.

So it wasn’t a surprise when the demonstrations began to take on a more sinister identity, when the conditions of these social and economic disparities would then give rise to a broader coalition of political grievances rooted in resentment and discontent.

These are the risks of having segments of a population living in a milieu that feeds into the ideas that there exist grave social injustices, where the tent of these social preconceptions looms larger and becomes a magnet for numerous other plights that allow the entire movement to latch onto in order to broaden its membership. Soon or later, these demonstrations are frequently consumed by the very violence these marches were meant to avoid.

The Los Angeles Times noted in its July 7 edition that the “march was mostly peaceful. But later, some marchers turned to vandalism, smashing windows of more than a dozen storefronts, including a bank, a popular taco chain and a Starbucks.”

Suddenly, alternative interest groups soon hijacked the demonstration, co-opting the original cause to suit their own purpose. Large red banners of the hammer and sickle, the vanguard image of the Communist movement were introduced; protesters brandishing Palestinian flags declaring genocide; burning effigies that resemble the U.S. President Donald Trump, torched in the central parque of the Mexican capital; and anti-I.C.E. demonstrators protesting the U.S. crackdown on undocumented migrants on U.S. soil.

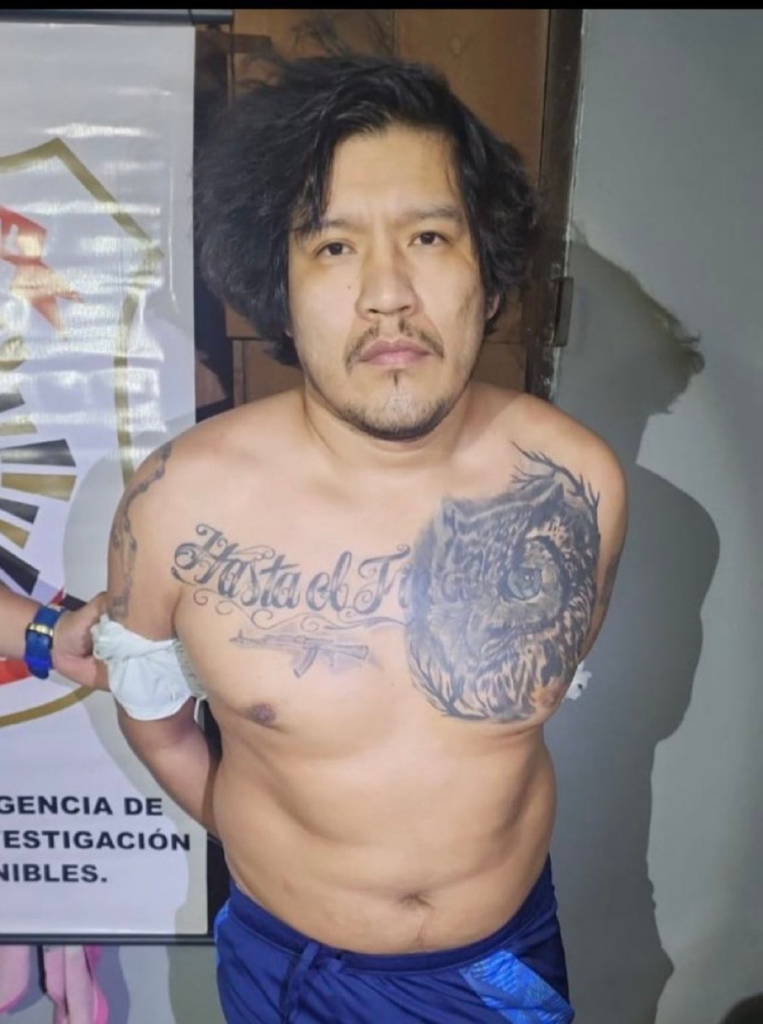

As the day drew on, the violence became more menacing as activists targeted small bistros in the La Condesa neighborhood, smashing the windows of coffee shops and local eateries that anchored advertising signs lettered in English. “Here we speak Spanish” wrote one defilement, and “Kill a gringo” one piece of graffiti read on a wall of an apartment structure. Spray-painted vehicles with vulgar pejoratives written on the hoods. The videos were splashed all over social media, as the demonstration’s original message to the Mexican government was no longer vivid.

President Claudia Sheinbaum held a press conference shortly following the “gentrification” protests, where the president was asked for her thoughts on the matter. Sheinbaum denounced the demonstrations, calling them “xenophobic”, and assured the press that “Mexico is an inclusive country.” She continued, however, by saying that the problems that are of concern to the native population need to be addressed.