The darkest period since Peruvian independence has been marked by two decades of internal conflict from 1980-2000, when communist guerrillas swept through the remote mountainous terrain of the Peruvian dry-lands and moist jungle fields beneath the heavy canopies of the territorial Amazon.

The state security forces of the central Peruvian government were deployed to stamp out this insurgency, formed by a Maoist cadre of student revolutionaries who were inspired by the Cultural Revolution in China, and later turned the Peruvian countryside red with the bloodshed of tens of thousands of mostly poor indigenous peasants.

The revolutionaries, however, were not alone in the bloodletting. The Peruvian government also engaged in extrajudicial killings of barbaric proportions.

The troubling lore of battalions of government death squads and their perpetrations so closely mimic the transgressions that occurred throughout the entire hemisphere during the latter half of the second part of the 20th century.

El Salvador, Nicaragua, Colombia, and Guatemala, where university students dreamt up lofty visions of revolutionary utopia, roused by decades of economic oppression and exploitation, sought to displace the large landowning political establishments of Latin America, but were soon mowed down by government forces. Nicaragua was one of a few that succeeded.

Almost 70,000 people were killed in the Peruvian Civil War; the same number fell in El Salvador; tens of thousands in Colombia; 150,000 killed or disappeared in Guatemala; 60,000 in Nicaragua. In Peru today, some 20,000 presumed victims of the killings are still listed as “disappeared”.

According to Peru’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was established by President Alejandro Toledo to investigate human rights abuses committed during the internal conflict, more than 4,000 clandestine graves are estimated in the country as a result of the political violence that occurred during this 20-year period.

Peruvian rebel groups, like the Movimiento Revolucionario Túpac Amaru (Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement) – MRTA, and the more notable Sendero Luminoso, Shining Path, a Marxist-Leninist guerrilla organization that was started by a professor of philosophy named Abimael Guzmán, first as a university student organization arguing for socialist policies and more representative government, until it then launched its “People’s War” against the state and declared itself the “vanguard of the world’s communist movement.”

As the Shining Path grew in influence, manpower, and support from the rural peasant populations, the Peruvian military forces developed a plan to arm and train some of these local populations who chose to align themselves and their communities with the central government.

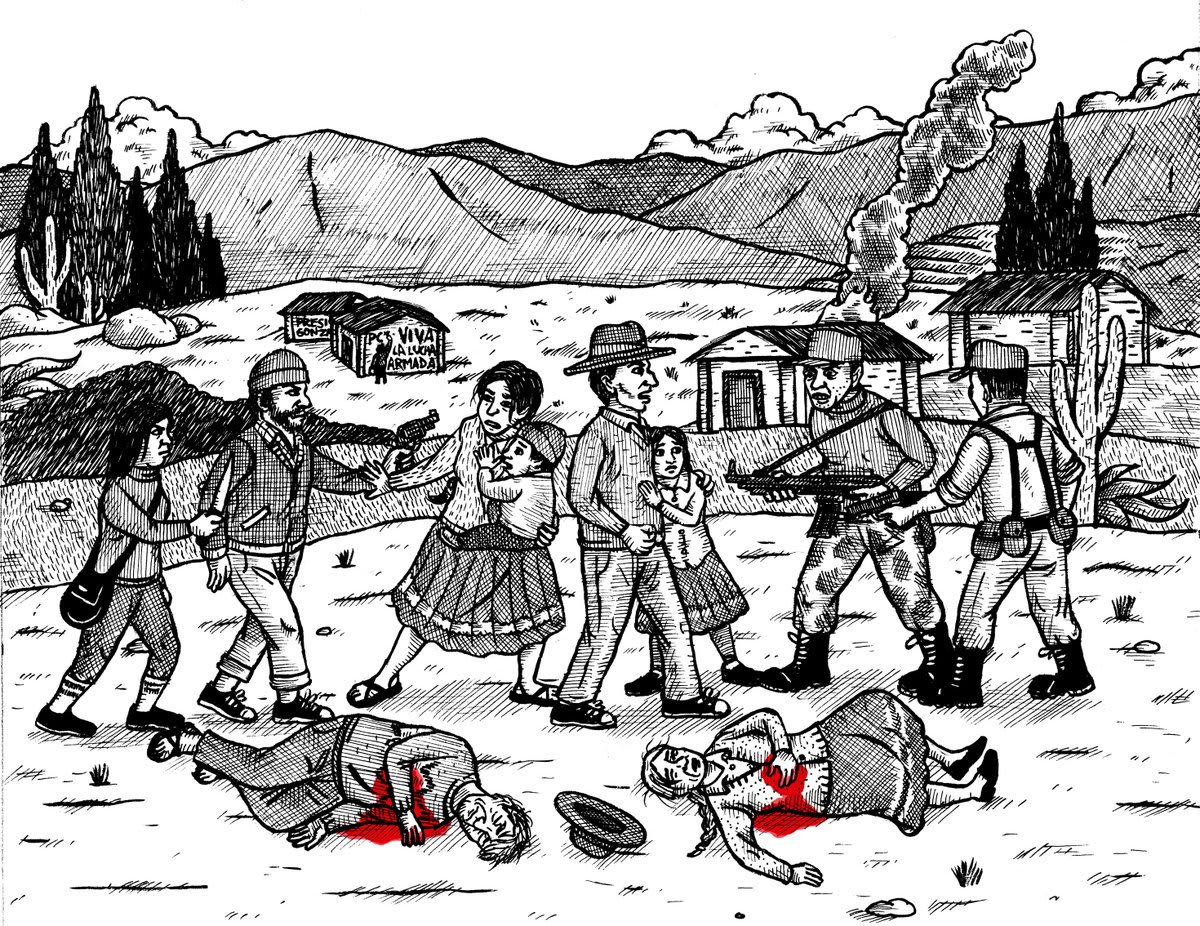

These groups of local civilian militias became known as the Rondas and were provided a level of autonomy in their fight against the guerrillas. Several instances led to the brutal killings of rebel leaders of the insurgency and suspected insurgents that fueled a vicious cycle of violent civil terror between anti and pro-government forces.

The Peruvian armed forces also engaged in tremendous horror. At the start of the internal conflict, the Peruvian government regretfully underestimated the willingness of the Shining Path for violent revolution. The group boasted of only about 500 members, and the Peruvian military command believed that the guerrillas could be eliminated by a small police force. However, as support for the communist cause spread throughout the rural mountainous regions, the central military apparatus of the central Peruvian government resorted to more professional means, deploying large amounts of trained soldiers to unleash a reign of terror in the countryside.

Units of the Peruvian armed forces were afforded great leniency in their counter-insurgency operations and detained civilians who were merely suspected of rebel activity. Horrific crimes of arbitrary killings and mass rape by government forces only exacerbated this cycle of violence.

The Shining Path reciprocated the violence by indiscriminately murdering villagers who were suspected of cooperating with the Peruvian government, systematically burning and looting local communities, house to house, and killing dozens of villagers and small children with sticks, axes, and hatchets. One episode, later referred to as the Lucanamarca Massacre on the 3rd of April, 1983, demonstrated to the Peruvian government that, in the words of the Abimael Guzmán the leader of the guerrilla movement, “the Shining Path would be a tough bone to gnaw.”

Human rights groups, families of thousands of victims, and prominent leaders of the international community are outraged this week after the President of Peru Dina Boluarte, signed into law a bill that was passed by the nation’s congress last month that grants amnesty to thousands of police and military personnel and officers, including individuals in commands of the civilian-led, anti-insurgency self-defense groups, the rondas, who have or may be accused of human rights violations during the internal conflict of 1980-2000.

The nation’s top military brass and the conservative establishment of Lima’s central government have been urging this move for years. The irony of this development lies in the fact that Dina Boluarte of the far-left Marxist Perú Libre party signed off on the bill.

The legislation will specifically prevent the criminal prosecution and conviction of former soldiers, police officers, and self-defense committee fighters accused of serious human rights violations in the country’s fight against leftist insurgents of the Mao-inspired Shining Path, including various other rebel groups.

Last year, Peru’s congress approved a bill establishing a statute of limitations for war crimes and crimes against humanity committed before 2003, shutting down thousands of investigations into allegations of war crimes committed by anti and pro-government forces.

Peru’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) also found that members of the Peruvian Armed Forces were responsible for 83% of the documented sexual violence cases during the internal conflict.

Although the events of the Peruvian Civil War occurred almost a half century ago, its memories are still fresh in the minds of many Peruvians whose wounds have now been reopened with Boluarte’s executive order.

Tens of thousands of families, many of which are the descendants of innocent civilian victims of the bloodshed, have fought long and tiresome struggles to find those accountable for the country’s horrendous atrocities. A Human Rights Watch representative says that it feels all of that work was for naught.

Boluarte remarked at a ceremony for the signing of the legislation, “Today, with the enactment of this amnesty law, the government is paying tribute to the military and self-defense groups that participated in the fight against terrorism.”

However, human rights groups are calling the measure a betrayal. Representatives from the United Nations are puzzled by the actions of the Boluarte administration and are urging Boluarte to rescind the blanket amnesty of human rights violators.

In December of 2022, widespread protests erupted following the removal of President Pedro Castillo of Boluarte’s Perú Libre party after attempting to dissolve the Peruvian congress, when impeachment proceedings were being made against Castillo within the legislative body.

Thousands of Peruvians descended onto the streets to protest the ouster. The protests started small, but later grew and became more violent. The Peruvian government responded harshly, shooting live rounds into the crowds of demonstrators, ultimately killing 50 and injuring 1,400.

Families of those killed in the demonstrations pleaded with human rights groups, demanding justice for the indiscriminate murder of protestors by government forces. Boluarte’s amnesty bill will also be applied to those police and military personnel involved in the 2022 protests.