San Salvador, April 18, 2025 – It was late November of 1980, a week after a presidential election that was ostensibly in the bag for the Republican challenger, Ronald Reagan. Democrat incumbent Jimmy Carter – seeking his second term in the White House – was gasping for air in the final weeks of the race, embroiled in crises that would later define an administration that was to say the least, disappointing.

Carter’s negotiations with the Soviets on the SALT (Strategic Arms Limitation Talks) treaties, which were designed to limit the overall nuclear arsenals of both nations, fell apart in the last weeks of his administration.

Agreements were reached between the two governments in June, but the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan six months later pushed Carter to remove the treaty from Senate approval in January of the following year. The Carter administration was also reeling from extremely high levels of inflation arising from an energy crisis that caused increased prices and fuel shortages nationwide.

The Iran hostage crisis was also an ongoing humiliation. The Panama Canal deal in 1977 that involved the Carter administration returning ownership of the property – a critical geo-strategic chokepoint for global trade – to the Panamanian government for a bargain price of $1 aroused widespread derision from members of Congress of both parties, albeit more vehemently from his more conservative critics.

Crises were all coming to a head when a little revolution began to sprout in Central America. Since 1977, the Sandinista National Liberation Front had been gaining ground in Nicaragua. An insurgency to overthrow the dynastic dictatorship of Anastasio Somoza, long-time ally of the United States, was starting to make major advancements against the capital of Managua by the end of Carter’s term.

The Sandinistas were a communist guerrilla group inspired by the revolutionary success of Castro’s Cuba, hell-bent on liberating Nicaragua from what they saw as U.S.-led capitalist imperialism and state repression with a vision of implementing their own dreams of a Marxist utopia.

By late 1980, negotiations between the Carter administration and the Sandinista command cadre led to Somoza stepping down with the inevitable takeover by the communists. The unraveling of stability throughout the world and the growing concerns of Soviet influence in their own “backyard” demonstrated to the American voters the belief of weakening U.S. dominance globally, originating from an administration that did not appear capable of meeting the growing challenges.

In late January of 1981, Ronald Reagan was sworn in as President. Upon entry into the White House, the Iran hostages had been released, but a more pressing issue was demanding the urgency from the new administration. Reports were coming in that the now victorious Sandinista forces of Nicaragua, with aid from the soviets, Cuba, and Vietnam, were facilitating the flow of weapons and equipment in support of a nascent revolutionary movement in neighboring El Salvador called the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front. This was another communist guerrilla movement with the same dreams as their Nicaraguan brothers to the south, to overthrow the U.S.-backed, oligarchic regime of wealthy Salvadoran landowners and implement their own communist government based on the principles of Marxist-Leninism with the mighty Soviets as their vanguard. The Domino Effect was still alive, and the communist threat was spreading further north.

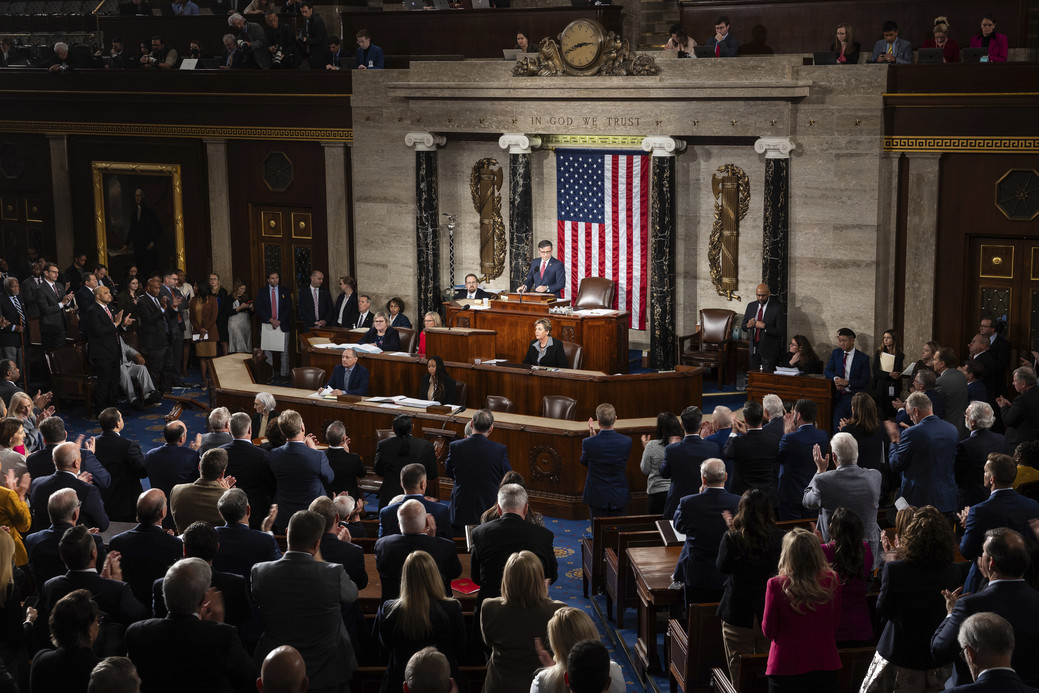

Now 45 years later, not long after Donald Trump made his return to the White House in January of 2025 to initiate his second term as President – and in the wake of a similarly disappointing and impotent Biden presidency that was strained by inflationary troubles and destabilizing events abroad that echoed the turbulent years of the Carter administration – El Salvador too, became a significant focal point for the new administration.

Both Reagan and Trump, from the start, set out to embark on a different course to implement their foreign agendas. Both wanted a more aggressive role to be played by a resurgent U.S. superpower, one that would make its return from the timidity and insecurity that marked the tenures of their predecessors. But the circumstances are very different, of course.

During the Reagan years, left-wing politics were taking Central America by storm. Today, it is right-wing politics – to a lesser extent – that is stealing the headlines. El Salvador has come a long way from its revolutionary years. Today, its concerns are of the rule of law and public safety after years of violent crime and exorbitant murder rates that were unrivaled in the entire world in 2016.

During the 1980s, Reagan was trying to orchestrate an appropriate response to minimize a spreading communist fervor. Today, Donald Trump is attempting to repair an immigration system that for the previous four years was largely unenforced and exploited by Central Americans in search of greater opportunity in the United States, but also by unscrupulous criminal organizations and bad actors looking to take advantage of North American leniency.

Part of this immigration crackdown has garnered international attention and condemnation, mainly from liberal politicians and human rights organizations. At the center of the controversy is El Salvador’s newly built Terrorism Confinement Center, known as CECOT, a 23-hectare compound designed to house 40,000 inmates, and one that is currently being used to confine some of the most dangerous criminals in the Western hemisphere.

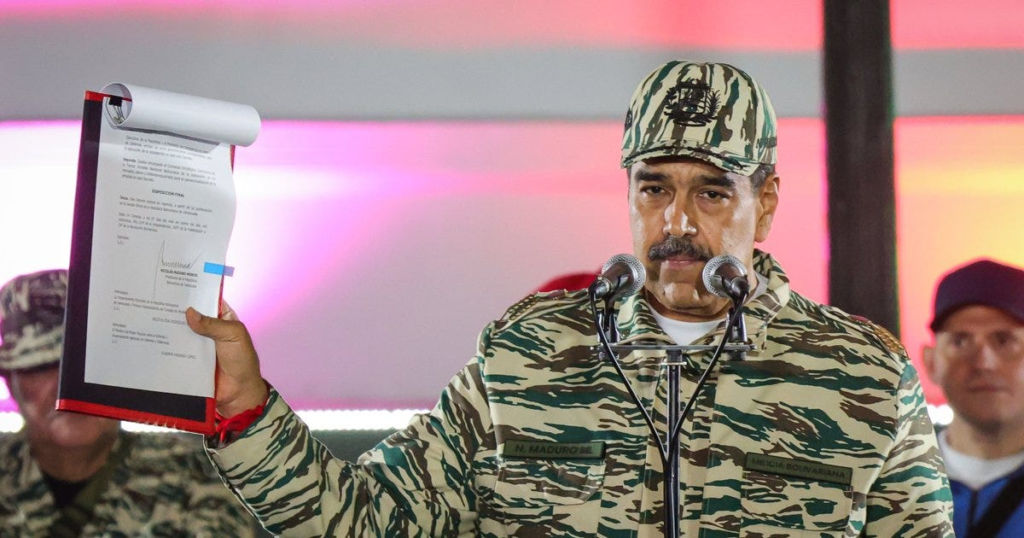

El Salvador’s president Nayyib Bukele arose from obscurity in 2019 by promising the Salvadoran people a return to law and order, and clamping down on the criminal organizations and the maras, or gangsters from the notorious MS-13 street gang that ruled the Salvadoran streets with impunity for nearly two decades.

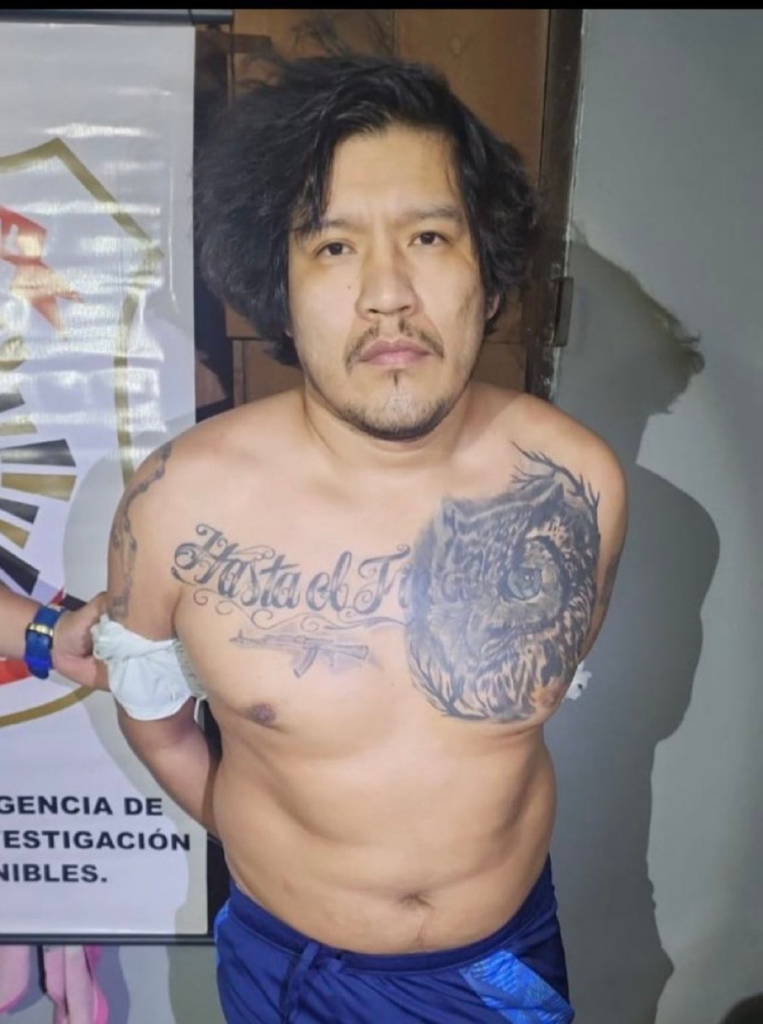

One particular individual named Kilmar Abego Garcia, an illegal immigrant residing in the state of Maryland, and a twice federally adjudicated individual with ties to MS-13 was deported back to his country of origin in March, and is currently being detained at CECOT, El Salvador’s maximum security prison. The story has been in the headlines since attorneys representing Garcia, along with his family members, have publicly pleaded with the Trump administration to release him back into the United States.

During a brief visit to the White House, Bukele was asked what he intends to do with Garcia as calls mount for his release by prominent members of the Democrat Party, Bukele responded by asserting that Garcia will remain in Salvadoran custody.

On Wednesday, the 16th of April, Senator Chris Van Hollen, Democrat of Maryland, traveled to El Salvador in an independent foray in opposition to official White House policy to attempt to meet with Abrego Garcia and to verify whether Garcia is afforded proper treatment by Salvadoran authorities. Van Hollen reportedly met with Salvadoran officials shortly after his arrival to obtain Garcia’s release. However, officials advised the Senator that proper channels must be heeded, i.e. the U.S. ambassador’s office.

On the 17th, Van Hollen was granted a meeting with Abrego Garcia, who appeared in good health.