For the last 75 years, Costa Rica has been the shining exemplar of peace, stability, and democratic governance in a region spoiled by the opposite.

Central America over the last century has been largely defiled by incessant civil strife, corruption, coups and instability, rebellion, bloodshed, poverty and violence unrivaled by the rest of the world in certain periods of this epoch.

Costa Rica, on the other hand, managed to walk away considerably unscathed from these domestic maladies, with much attribution awarded to its enlightened foresight in good, representative government, especially during and after the Second World War, owing much to its standing as one of very few nations in all of Latin America, which can sincerely claim to be one the most successfully governed states in the entire Western Hemisphere.

Her other Isthmian neighbors have been tormented by civil wars and massive upheaval, and government instability for much of the 20th century.

Honduras was mired in administrative chaos during much of the first half of the century and into the 1950s as the masses were tirelessly dragged and twisted by the various cults of personality that so happened to woo the day, rather than the validity of the ideological principles thoroughly proposed by its political parties.

The trend of catapulting certain individuals to the privileged position of total power was known as personalismo, where parties were more aptly characterized when supporters followed the man, rather than the idea. The people, unfortunately, were undoubtedly no better served simply because their local leaders had more machismo.

Guatemala, sliced and diced by its mixture of race and heritage, was miserably divided by the ruling White, Spanish-descendant elites and the overwhelming masses of Indigenous natives who were much darker than their new overlords (and much poorer). The racial issues were exacerbated by a crushingly unequal land ownership disparity that eventually led to a rise in communism, revolution, violence, and a civil war that lasted for 30 years, killing tens of thousands.

El Salvador didn’t escape the bloodshed either, ravaged by their own internal revolt, and the communist Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front that launched a full-throated guerrilla insurgency against the U.S.-backed and U.S.-funded government forces led by a wealthy land-owing, military-oligarchy, which, in 1960, made up roughly 2% of the nation’s population, and yet controlled over 80% of the country’s arable land.

El Salvador – resource-rich but land-poor and overpopulated – animosity and resentment towards an obstinate, wealthy ruling class who simply refused to compromise on the smallest reforms demanded by the poor and miserable masses, suddenly boiled over in 1979, in one of the nastiest battles in the entire Western region, leading brothers against brothers, sons against fathers, and fathers against sons in a brutal civil war that lasted for 12 years, killing 75,000 soldiers and civilians, from a population of only 4.5 million.

Nicaragua was just as bad, lasting for 15 long years. The battle lines were drawn along the same reasons, however, its revolution was much more successful, and yet the poor Nicaraguan people still suffer today from the repressive Marxist-Leninist stranglehold that reached their throats over 45 years ago.

Costa Rica was different – its first significant political achievement was stability in government with an orderly succession of presidents for eight years (something unseen in Central America during this period) under a constitution of December 1859, which established a three-year term for presidents.

Tomás Miguel Guardia rose to power in Costa Rica during the 1870s. Guardia was a dictator but was more enlightened than his Central American counterparts throughout the Isthmus and was able to execute on the liberal ideals that interested other leaders in Guatemala and Honduras, who were unable to do the same due to incessant internal discord.

Guardia ruled Costa Rica for ten years and oversaw the expanding industrial development of his country’s infrastructure and railway lines that propelled an unrivaled economic growth in the region. Constitutionalism and stable government continued for another 30 years after Guardia’s death.

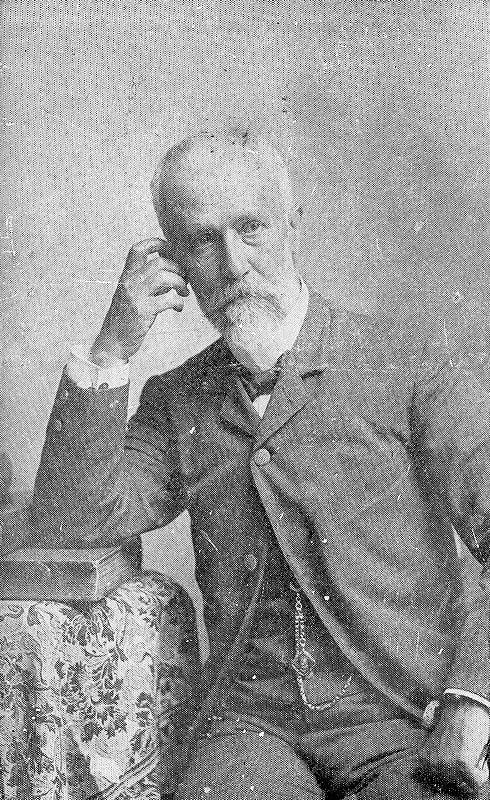

In the late 19th century, Mauro Fernández, a minister in the Soto administration, was a pioneer and leading thinker of his day, and he created a system of free and compulsory public education in Costa Rica, thus planting the seed that eventually inspired a student enlightenment in the 1940s that helped to establish the most prosperous country in all of Latin American by the half century.

The program reduced the national illiteracy rate, something which had plagued the entire region since its inception, and gave birth to a nationalist liberal framework of consciously enlightened, representative, and stable government, buttressed by the progressively democratic and successively conservative administrations of President Ricardo Oreamuno and Cleto González Víquez.

These two presidents were deeply progressive-minded, instituting substantive reforms for the Costa Rican people – reforms in education, social welfare and security, land distribution, and wages and employment security – but these men are also revered today by the conservative elements of the Costa Rican political establishment for representing a stability and forthrightness in government during a tumultuous period in the 1930s-1940s that was defiling the other peoples of the Isthmus with dissension, civil discord, and violence.

From the post-World War II era onwards, the Costa Rican political situation hardly resembled that of its neighbors. Costa Rica saw a rise of a workers-inspired communist movement in the Vanguardia Popular (Popular Vanguard), but one that was moderated without the calls for violent revolution as witnessed in El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala. The Costa Rican communist party never gained tremendous political power, partly as a result of the visionary leadership of the nation’s progressive statesmen of the early 19th century.

Costa Ricans were much more autonomous than their northern Central American counterparts; less dependent on U.S. imports; more homogenous than all of its neighbors; and without a standing army since 1949, after its constitution outlawed the the military as a permanent institution, an institution which had cursed the modernization of the other republics, and an institution which had been at the center of unending coups or golpes throughout the rest of the region.

This level of independence, along with a functioning and effectively representative democracy, has allowed Costa Rica to chart its own course. A course much different from the others in Central America. More luminous, more enlightened, and more developed.

Its pristine beaches, stable economy, and welcoming environment attracted travelers and nature gazers from Europe, Asia, and the Americas, until the country became one of the foremost tourist destinations in the Western Hemisphere. (Recent research studies in the country indicate approximately 60,000 residents are employed in the nation’s tourism sector, representing over 7% of the entire national workforce.)

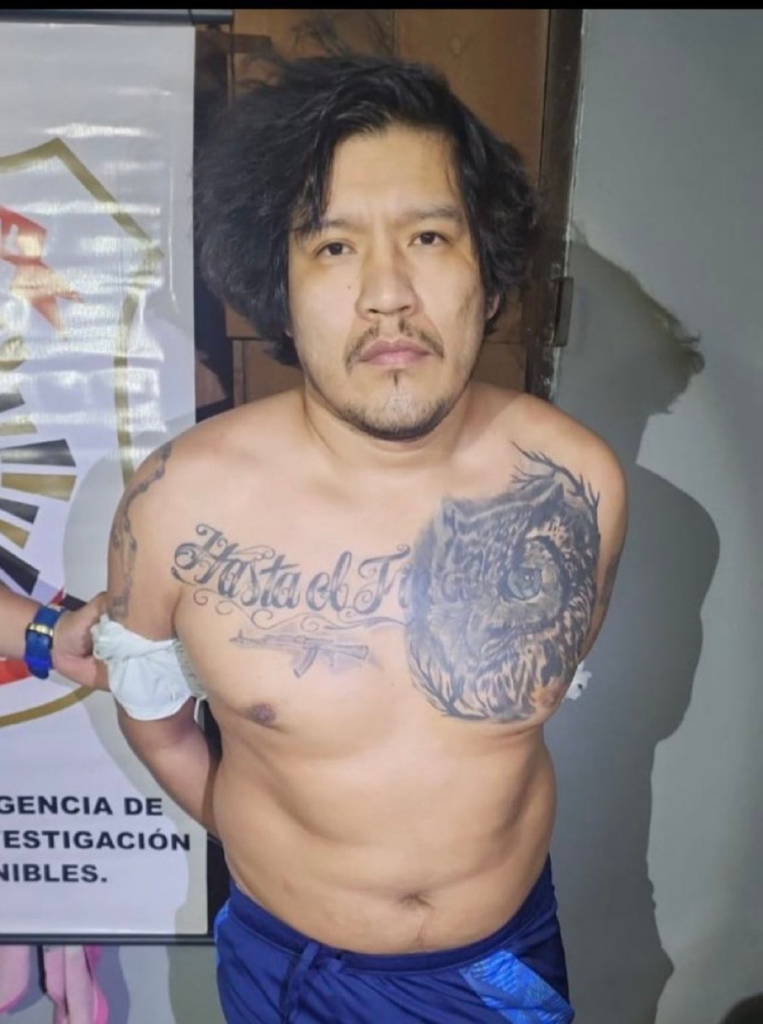

However, many of these travelers have become alarmed at the disturbing rates of violent crime, even in the typically busy, but soundly peaceful streets of the capital city of San José.

The nation is being rocked by a violent, drug-fueled crime wave that has resembled those of Guatemala, El Salvador, and even Honduras in recent memory. Usually detached from these regional afflictions tormenting its northern neighbors, in this regard, Costa Rica has been bitten by the same flea.