Managua, April 23, 2025 – This weekend marked the seventh anniversary of an uprising that took place in 2018 in Nicaragua’s capital of Managua when thousands of people began to clamor for the resignation of the wily dictatorship of Daniel Ortega, who originally climbed his way to power after the successful ouster of the U.S.-backed and longtime authoritarian dictatorship of Anastasia Somoza in 1979.

Ortega, who returned to power in 2007 after being pushed after being defeated in the 1990 elections, when international observers from the United States and representatives of OAS member-states (Organization of American States) were granted access to the newly implemented democratic process.

Violetta Chamorro, wife of Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Cardenal – who was a leading journalist in Nicaragua and heir to the national publication La Prensa, assassinated in 1978 – was elected in a landslide as Nicaraguan’s grew weary of democratic backsliding under the obdurate Ortega, miserable economic woes, and an 11-year civil war that raged between Soviet-backed Sandinista forces and U.S.-backed Contras that killed tens of thousands.

Violent transitions of power have been a common theme in Nicaragua since the nation earned its independence in the early 19th century. Almost every ruler or president of the Central American republic had been removed by the barrel of a gun. The elections of 1990 and the smooth transition of power from a Marxist Sandinista government to a moderate coalition of democratically-minded factions who opposed the Sandinista regime of Daniel Ortega for the past decade were a reassuring departure from the turmoil and constant chaos that plagued three U.S. administrations from Carter to Bush.

The Chamorro presidency marked the first time in five decades that a Nicaraguan president had entered power resulting from a free and democratic election, restoring a hopeful promise for a free and prosperous Nicaragua.

However, the new Chamorro administration would later be mired in crises of its own. Chamorro inherited an economy that had been destroyed by war and destruction, but the economic situation worsened under Chamorro as the flow of foreign funds and contributions began to dry up after the peace agreement became reality. As the “Nicaraguan Issue” was erased from the halls of Washington, American politics no longer felt concerned with the plights of the local Nicaraguan people. In the absence of the civil war, the small nation was simply no longer of any interest to anyone. There were bigger fish to fry.

On the domestic front, although Chamorro successfully piloted a peace process between the government and the now disbanded Sandinistas, and although she negotiated the voluntary relinquishment of Sandinista arms from former rebels, – who were once members of the ruling Sandinista armed forces and salaried employees of the Sandinista government – were now ostracized and faced the challenging prospects of transitioning from military state-rule to civilian capacities of peacetime Nicaragua.

Darker Nicaraguans of indigenous descent, or indios, the historically oppressed peoples of the region who made up a predominant element of the insurgent/rebel groups on both sides – Sandinista and Contra felt betrayed by the white, oligarchic elites, or the cheles.

Chamorro also embarked on an austerity program to reduce the nation’s public debt, causing lower wages and unemployment that drove a tremendous wave of protest from Nicaraguan citizens who eventually took to the streets to voice their dissatisfaction with the reform initiatives and failing economic prospects of the new government.

The Chamorro government must’ve considered the potential return of the Sandinista movement if it had failed to deliver the results promised to its constituents. But the Chamorro administration was perhaps comfortable in the assurance of the inevitable promise of democracy sweeping across the region following the collapse of the Soviet Union. Or even perhaps the administration was guilty of the same mistake Ortega made in 1990 and was simply blinded by the confidence in their own power, so completely detached from the moods of the Nicaraguan people.

In 2007, Daniel Ortega then made his long-awaited return to the presidential house in Managua after 17 years of an impotent anguish in which he was confident to never repeat the mistake in allowing any room for the democratic process to flourish once again.

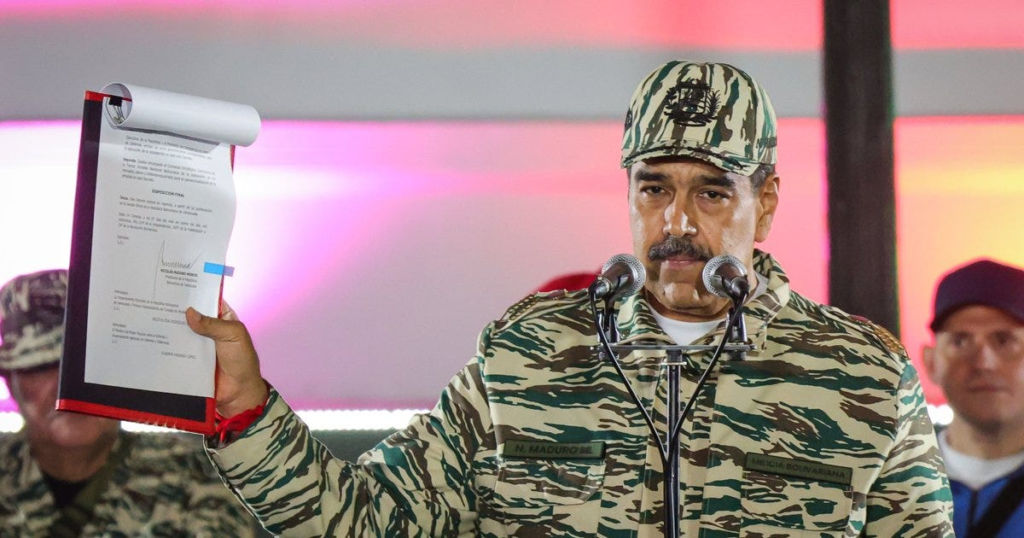

Upon retaking power, Ortega tightened his grip by seizing control of the nation’s legislative assembly and arbitrarily reforming the Supreme Court to remove any challenges that may be posed against his rule. Ortega also ramped up his crackdown on the nation’s press, censoring media outlets that criticized his agenda, imprisoning political dissidents, and banning any participation of opposing political parties against the Sandinista government.

In April of 2018, thousands of Nicaraguans took to the streets, clashing with state security forces and national police to protest reform measures on the nation’s pension system that a great many depend upon for subsistence.

Demands for Ortega’s resignation mounted. Las turbas, or the mobs, an organization of armed para-police elements were then unleashed onto the demonstrators, killing over 300 civilians in the melee.

Ortega has historically denied any claims of affiliation with the turbas. Many Nicaraguans, along with human rights organizations, claim otherwise.

Americans of Nicaraguan heritage also took to the streets throughout various cities across the U.S. over the weekend to commemorate the 2018 uprising, and the lives lost at the hands of government forces. The city of Los Angeles, where a large population of Nicaraguans currently reside, witnessed thousands of demonstrators taking to the streets demanding more freedom and the re-democratization of Nicaragua’s political institutions.

Roughly 450,000 people, as of 2021, who are of Nicaraguan descent live in the United States, representing one of the smaller Hispanic populations in the country, but nonetheless passionate. Many more in the homeland are desperate for change, and retain the hope for better days in Nicaragua beneath the heavy hand of an aging dictator.