Bogotá, April 4, 2025 – Over the weekend on the 3rd of March, more than 1,000 Indigenous natives boarded their painted buses called chivas, adorned with native decor and brightly dyed carpets of tribal custom, tumbling up the rugged mountains of Colombia’s capital.

They arrived from the rural southern departments of Cauca, Putumayo, and Nariño just north of the shared border with Ecuador.

These regions have had a long and tumultuous history of rebel occupation and bloodshed. For the last 65 years, violent clashes between armed guerrillas of Colombia’s revolutionary movements and brutal security forces of the Colombian state have been ravaging the rural country-sides pitting poor peasant campesinos against this violent backdrop and uprooting their families and livelihoods from their ancestral homelands.

Some of the more marginalized populations to have suffered from the turmoil of violence have been the native Indigenous people of Colombia’s rural hill and forested regions.

Historically repressed and unrecognized by the state, Indigenous Colombians are far more underrepresented than other constituencies who have played a more historically comprehensive part in the socio-political structure of Colombian society.

The troubles of the indigenous peoples of this region have their origins in the Spanish colonial era. Today, there are about 80 different Indigenous groups within Colombia, and each one has their own culture, customs, mores, and structures for their individual and collective lifestyle. Sixty of these groups have retained their own languages, further complicating any efforts for potential future assimilation.

During the 1960s, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), one of several rebel groups founded during this period sought to implement their own “Agrarian Reform Programme” that would help facilitate the redistribution of land to the poor, rural campesinos and institute an autonomous land system structured on the principles of social equality and justice.

According to the programme, the Indigenous communities, who already occupied their historical lands were promised protection by the FARC and assured that they would remain independent from the revolutionary movement. However, the FARC often betrayed this promise, making frequent incursions into Indigenous territory, and appropriating native land for their own use to conduct military operations against the state.

The FARC has also confessed to slaughtering eight Indians from the Awa tribe in the southern department of Nariño in February of 2009 because of perceived collaboration with the Colombian military. The Awa, however, accused the FARC of killing dozens more during the massacre.

Recently, violence has escalated since the reemergence of armed rebel groups after the power vacuum that was left when the FARC signed a peace settlement with the Colombian government in 2016.

Earlier this year, the ELN conducted a major offensive to expel rival groups from the Catatumbo region where coca cultivation has proliferated over recent years. Over 60,000 civilians in the area have been displaced.

The Ejército de Liberación Nacional (ELN) and the Ejército Popular de Liberación (EPL) – two groups of Marxist origin founded in the 1960s revolutionary movement – Los Rastrojos, as well as FARC dissidents of the 33rd Front, and the Gulf Clan have all been vying for control over the lucrative drug trade that transgresses the southern Colombian regions from Ecuador and Peru.

The violence has soared recently whilst the Colombian government of President Gustavo Petro promised the people of Colombia during his campaign that he would introduce a new era of peace and tranquility by reopening negotiations with the rebel groups.

Petro was elected president in 2022 and peace seems further away than ever.

On the 3rd of March, 2025, the people of Bogotá were greeted in the morning with a wave of their own clashes on the streets of the nation’s capital.

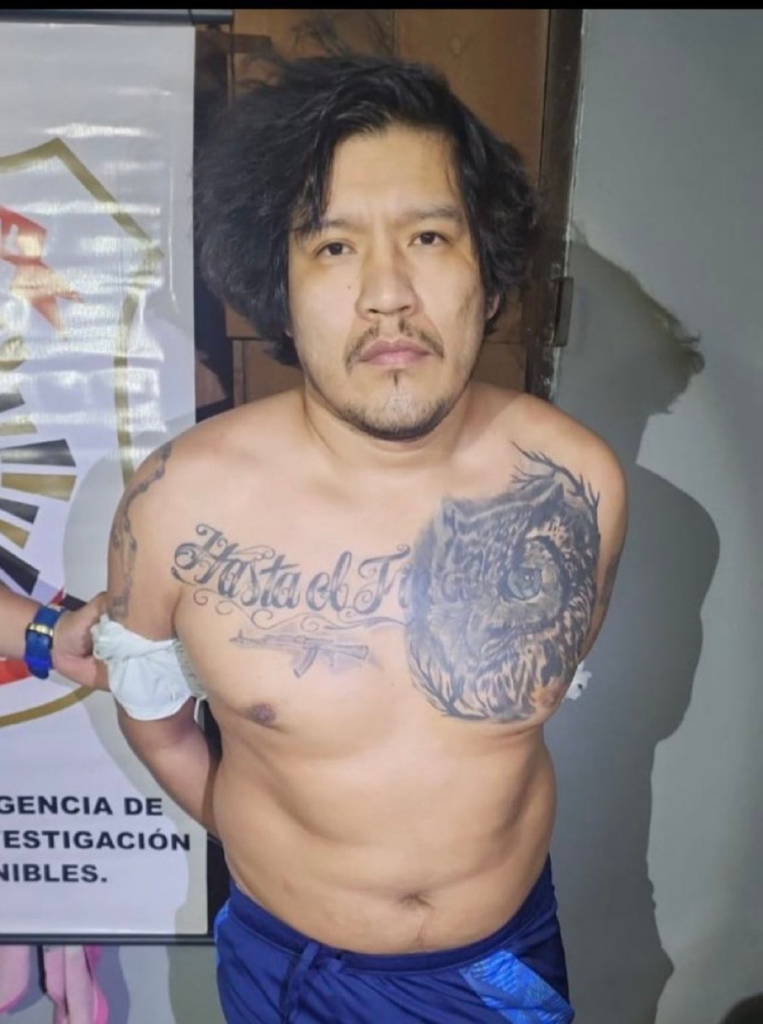

Over the last few days, Indigenous natives from the Misak, Inga, Kamsá, Nasa, and Guambiano peoples of the southern regions have been camping out of their buses and makeshift tents throughout Bolívar Square to protest the shortcomings of the Petro government to end the violence.

Today, demonstrations escalated when members of the groups started establishing roadblocks along the heavily trafficked streets of Bogotá, obstructing motorists and vandalizing buildings and the city’s public transportation system.

Representatives of the various Indigenous groups say that they do not feel represented by the Colombian government and demand negotiations with the central administration to reestablish peace in their regions.

Local bogotanos throughout social media were angered by the disturbances, many claiming that the Indigenous protesters were “impersonators” pretending to be natives, who were there in the city to simply start trouble and destroy property that doesn’t belong to them. Others ordered them to “go back home.”

In the meantime, the representatives of the Indigenous groups made it clear that they intend to remain in the nation’s capital until they are heard from.