The streets will remember it as the Motoboy Revolution, when young, ambitious, and hard-working motoboys of the nation’s food delivery services parked their bikes on the curb and took to the streets of Rio to demand better treatment from customers, and safer working conditions when feeding the hungry masses of Brazil.

Their movement resembles the Newsboy Revolution in New York City during the early 1900s, when the Big Apple’s largest newspaper distributors lowered the prices for their dailies, pushing thousands of newsies out of business in the city when profits were squeezed, leaving nothing left for the young newspaper couriers and without work.

The newsboys went on strike and refused to deliver their goods, cutting off the flow of information in the world’s financial capital.

Now, 125 years later, and 2,500 miles south of the Equator, tens of thousands of small-time food delivery drivers who operate mostly on motorbikes whiz through the unforgiving streets of Brazil, dedicated to feeding the millions of hungry mouths who want their food for cheap, and they want it fast.

For the drivers, they’re also committed to making a few Reals, come rain, lightning, and thunder, and the countless mishaps and near-death situations that blow down their necks every inch of the way.

On Friday, the 29th of August, one driver on a motorbike arrived at a residence to carry out an order at the Merck condominiums in the Taquara neighborhood in Rio de Janeiro.

The customer allegedly ordered the courier to deliver his meal to his apartment upstairs. The courier refused. An experienced courier knows all too well that there have been instances in which countless drivers have been lured to dark and cornered places to supposedly follow through on an order, only to be robbed at gunpoint and deprived of their belongings.

Moments later, the customer who made the order came downstairs to confront the courier and express his disapproval of the delivery boy’s stubbornness.

The courier cleverly took out his mobile phone to record the encounter, when the customer suddenly became even more agitated and began waving his pistol around, attempting to frighten the courier into delivering the food upstairs. But the courier didn’t budge.

Then, in a shocking moment, the customer pointed his firearm at the courier and shot him in the foot. Thick, frothy blood began to ooze from the courier’s wound, seeping into the asphalt of the residential street. The camera of the courier’s cell phone captured the whole episode in real-time, and would later be posted on social media, enticing the workers of an industrious delivery niche to protest the ill-treatment received by Brazil’s hardy customers.

Earlier this year, April witnessed the largest mobilization of food app delivery workers in São Paulo since demonstrations took place in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic.

A 48-hour strike occurred simultaneously throughout major cities in Brazil, where large convoys of motoboys headed towards the city of Osasco, where the headquarters of the largest app delivery company in the country, iFood, was located, to demand better pay from the platform’s heads.

Thousands of workers took to their bikes to argue for a modest increase in the minimum rate per ride, from BRL 6.50 ($ 1.14) to BRL 10 ($ 1.75), among several other compromises, including an increase for each kilometer traveled per delivery.

The workers vowed that if their demands were not met, the demonstrations would continue, and the strikers would prevent all deliveries from being carried out from the city’s biggest malls.

One leader of the demonstrations in April stood atop a truck with a loudspeaker: “This is people’s revolt. This is workers’ revolt!”

A banner nearby read: “Billions for iFood, crumbs for delivery workers”

Another banner warned: “iFood, Rappi, 99 and Uber: parasites promoting modern slavery.”

Protesters also shared grievances over the unsafe working conditions. Not to attribute blame for all of these conditions to the app service, because many of these conditions are often natural and come with the weather, and the dangers of the road, which are inherent in driving.

However, the demonstrators urged that if they had received better pay, workers wouldn’t be compelled to work so many hours, which leads to exhaustion and lack of focus. The reality of the conditions is simple: the more time spent on the road, the higher the likelihood that workers will have accidents.

According to a recent survey by the State Traffic Department, motorcycle deaths in the city of São Paulo alone increased by 40% in 2024.

The couriers do what they can to work around their troubles.

A meeting between iFood representatives and a small commission of organizers elected to lead the negotiations for the couriers ultimately fell apart, whereby the company refused to accommodate the demands of the strikers.

Although the problems ailing Brazil’s food app workers have mounted not only from the app services, but also from the state. Poor infrastructure and unserviceable road conditions make it almost impossible for a courier to go through an entire working day without having to replace a tire.

The majority of couriers in Brazil use their personal means of transportation, naturally. The overwhelming lot of them use motorbikes, and that makes it challenging for drivers already on the clock to avoid the devastating sea of potholes and cracked roads, to scurry past these death zones to deliver their meals.

Other couriers don’t mind the infrastructure at all and make do, but are more in fear of encountering a rabid lunatic ready to chew their heads off if an order isn’t accurate. Many drivers say they are treated like trash and are hardly respected by the customers.

An international survey found that over 70% of Brazilians either witnessed or have been involved in road rage incidents. Brazil also has one of the highest rates of traffic accidents than anywhere else in the world, with five people dying every hour in Brazil as a result of conflicts related to intolerance and emotional instability behind the wheel.

Armed traffic robberies, moving-thefts, and shootings my moving vehicles all rate high in Brazil.

‼️ WARNING: CONTENT ⚠️ Video of shooting of iFood Courier, Rio de Janeiro

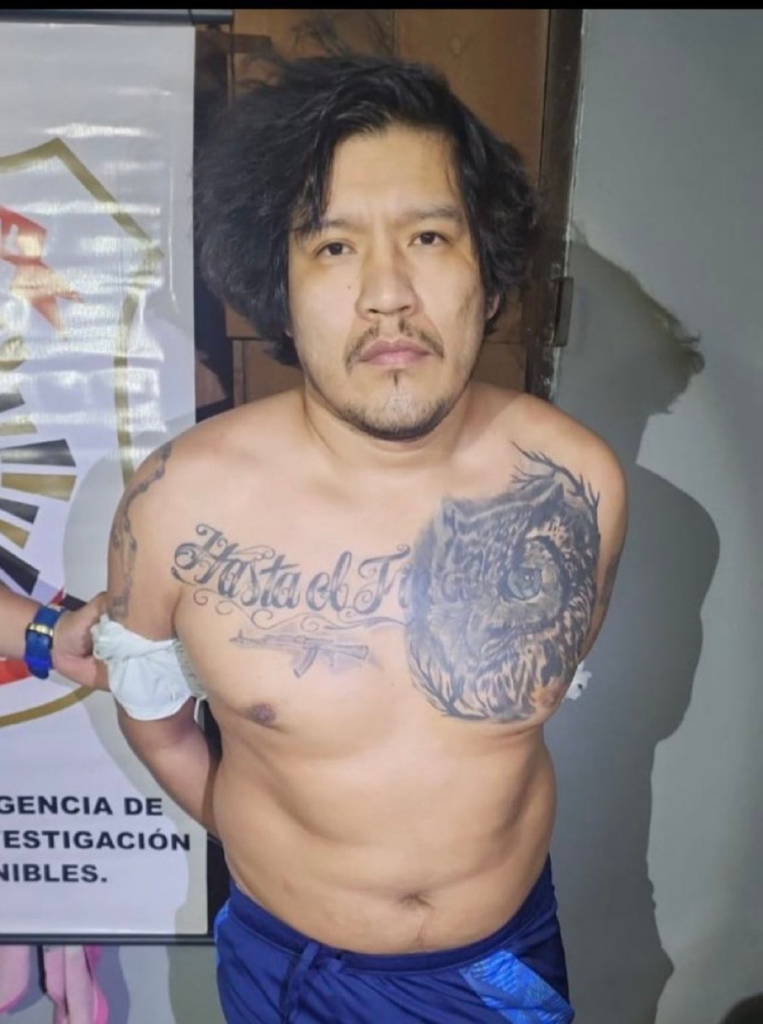

Suspect – José Rodrigo da Silva Ferrarini (Below)

Once couriers reach their destinations, they are often met with vitriol and criticism, and even with violence.

After the incident on the 29th, in the Merck condominiums in Rio de Janeiro, social media reaction to the courier, Valério Souza Júnior, being shot by a customer spread like wildfire. Drivers demanded justice, even arriving at the shooter’s home (inspiring the cover photo of this article). When the public temperature seemed to boil, authorities finally stepped in and arrested the suspect, a prison guard, José Rodrigo da Silva Ferrarini, who is in jail awaiting updates from the judicial system.

The victim’s legal team is urging for the suspect to remain behind bars as part of preventative detainment, while couriers around the country are applauding their efforts in demanding the arrest of someone who perpetuated acts of violence and unacceptable disdain toward a small but hard-working element of Brazilian society.

For the motoboys, their battles continue, for better pay and safer conditions, one kilometer at a time.