The most recent deportation campaign of Haitian migrants has roots in racism. Or is it a pis aller, and the last logical response by a nation unable to sustain the massive inflow of neighboring migrants?

An island shared by two, Hispaniola had been the prized possession of the colonial powers during an era of incessant quarrels over the lucrative West Indies sugar trade.

After the French were ousted by a most violent rebellion for liberation led by the prominent black slave leader turned General, Toussaint Louverture, the territory that made up the western third portion of the island was returned to the Spaniards until 1822, when Haiti had usurped total control of the entire territory of the island.

In 1844, the Dominican Republic gained independence from the Haitians, establishing their own form of government predicated on the old Spanish customs of their former overlords.

The sugar industry was big business in the new republic, but the large Dominican estate owners and the creole descendants of the Spanish aristocratic planter class, like many other colonies throughout the Caribbean, suffered from a shortage of labor, which had to be supplemented elsewhere by way of the constant influx of African slaves into the region. Many years later, the Dominicans had utilized a system of advantageous immigration practices that capitalized on the massive supply of unemployed Haitian labor across the border – and profited from it.

The racial differences had always been present on the island of Hispaniola, even before the departure of the European colonialists from the West Indies. The Dominicans, the descendants of white, Spanish progenitors, and the Haitians, the offspring of bonded black African slaves who labored over the cane fields for centuries, shaped an overwhelmingly discernible framework for a bipolar preconception of how the island is to be divided in order to better serve – in their beliefs – the favorably endowed race of white-blooded Europeans of moder Dominica.

This framework, through the lens of a concept of antihaitianismo, helped to not only establish a system of a “white supremacist justification for a racialized division of labor”, but codified it to then be enforced by subsequent Dominican governments for capitalist exploitation.

Sagás E. Race pointed out that the development of this socio-ideologically racialization was borne out of Imperial Spain’s ideas of limpieza de sangre, or purity of blood. Later-Dominican governments and authoritarian dictatorships used this perceived justification to aggressively carry out exploitative labor practices over Haitian migrants, and in conjunction with friendly U.S. governments to benefit American sugar companies for much of the early half of the 20th century.

In 1937, a caudillo by the name of Rafael Trujillo came to power and ruled the Dominican Republic as dictator. Trujillo, nicknamed “El Jefe”, The Boss, so adeptly personified this anti-Haitian racism that he used to apply make-up to his face in an attempt to whiten his skin. The Dominican authorities of this era also conducted field tests, according to a popular though unconfirmed story, on suspected Haitian migrants by ordering them to pronounce the word “perejil”, parsley. Because the Haitian Creole-speaking people had difficulty pronouncing the letter “R”, the exercise was used as a litmus test to determine their origins.

The hatred and anti-Haitian sentiment from the central Dominican government came to a head in the Parsley Massacre of 1939, where an estimated 14,000-40,000 Haitian migrants were slaughtered in settlements along the Dominican Republic’s northwestern frontier and certain parts of the Cibao region. Trujillo had gotten word of reports in which Haitian migrants were suspected of stealing cattle and livestock in the area, later ordering various elements of the Dominican military to carry out the wholesale slaughter of Haitians in the region.

Today, the raids are no longer in the sugar fields, but in less dramatic, now in the hospital wards of laboring mothers who are subject to deportation.

In 2013, the Dominican Supreme Court revoked the citizenship of children born in the country to parents who were not Dominican citizens. Dominican-born children, previously a qualifier for Dominican citizenship, were determined to be noncitizens virtually overnight, leaving not only these children, but also first and second generation Dominicans, now subject to removal proceedings by Dominican immigration authorities.

Human Rights organizations have condemned these measures, as well as the methods used to execute these deportations as violations of the civil liberties of migrant families and refugees fleeing the chaos and violence of war-torn Haiti. Maternity boards have reportedly been raided by authorities, grocery stores, and industrial warehouses where employers illegally hire undocumented labor to squeeze their margins. Other local Dominican leaders and government officials claim that the sheer volume of Haitian migrants is unmanageable, asserting that the Dominicans shouldn’t be the only people to shoulder the consequences borne out of the Haitian plight.

Other resident Dominicans voice similar concerns, urging the international community to play more of a role in managing the Haitian crisis. These Dominicans say that local resources are simply not there to help aid such a large amount of people seeking refuge in the Dominican Republic. Others fear that they are being pushed out by foreigners and noncitizens.

How much should other citizens and native residents of their own countries sacrifice to accommodate the comforts of other people? When is too much more than enough? How much security and succor is to be given up and forfeited in order to supplement the deprivations of other people? These are the concerns of the local Dominican population, and officials say that these concerns should be recognized by the international community, too.

The Belladère border crossing in the Dominican town of Comendador is one of four border crossings along the Haitian-Dominican border. Belladère has become the focal point of the Haitian migrant crisis. At the height of the Haitian migration, thousands of Haitians were streaming across this checkpoint, being processed by Dominican immigration authorities, and provided directions to migrant aid stations further east. Today, however, the caravans are heading west. Stumbling paddy wagons stuffed with Haitian migrants being shoveled back across the border into Haiti.

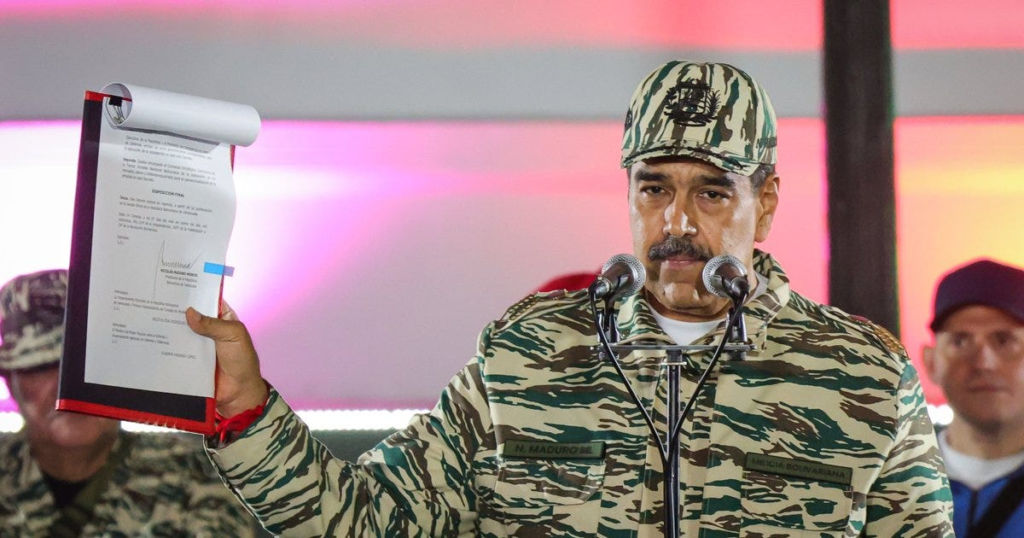

In October of 2024, newly elected President of the D.R. Luis Rodolfo Abinader Corona, issued a quota to deport 10,000 Haitian migrants per week from Dominican territory. Abinader campaigned on a tougher stance on the Haitian migrant crisis, and remains intent on fulfilling his promise. Locals have issued complaints against the government that migrating Haitians are taking local jobs meant for native Dominicans, as rising concerns over the Haitianization of the Dominican Republic are on the rise.

Many Haitians find employment across the border, participating in the seasonal work of various agricultural products. They have done this for years. When the season ended, these laborers would return home with proceeds to help provide for their families in Haiti. Next season, they’d do it all over again. But today, Belladère border crossing is only a one-way route, occupied by returning migrants no longer welcome.

A few decades ago, after the fall of Trujillo and the introduction of a more neoliberal socioeconomic framework, after the colonialism, the oppression, and the capitalist exploitation, many believed that the old anti-Haitian hatreds and prejudices were put to bed, and perhaps they are. But perhaps these anxieties were always present, only made dormant until the repeated catastrophes have plagued the Haitians in recent years.