Sweeping reforms are often best suited in times of crises, and the most recent election in Ecuador validated its incumbent with a comfortable victory, paving the way for Daniel Noboa, scion of a wealthy Ecuadorian business dynasty, in his second term to reinvigorate a nation shackled by fear, and a relentless crime wave that had taken the country by storm.

Ecuador’s divisive political landscape and growing distrust among opposing parties has been exemplified in the reaction of Noboa’s challenger, Luisa González, following the election, and her refusal to recognize the officially declared results, (even going so far as to allege them to be “fraudulent”, but is commonplace in Latin American politics).

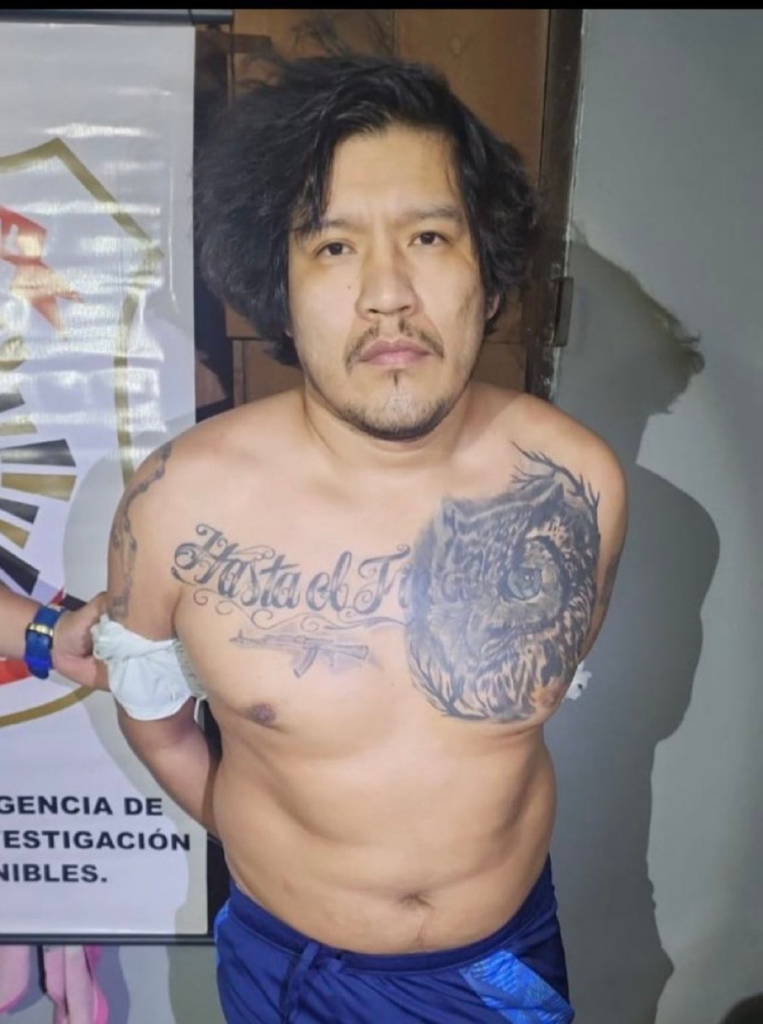

It was no surprise that Ecuador’s election was to be a controversial one, especially in the aftermath of the earthshaking assassination of popular political figure and presidential candidate, Fernando Villavicencio in August of 2023. The killing was later deemed to have been ordered by Los Lobos, one of the nation’s most ruthless gangs.

From the beginning, it was a hotly contested race between two very starkly different visions for the South American republic, and one that also resembled the feverishly passionate races so typical of Latin America. A race drawn between the traditional battle lines of the more right-wing, socially conservative, and strong on crime approach versus the left-wing, nationalist denouncement of the neoliberal economic order and its concomitant anti-American sentiment.

González, the country’s heir to former president Rafael Correa’s controversial leftist political platform, Citizen Revolutionary Movement, has been closely tied to Correa, painted by detractors as an indistinguishable extremity of Correa culture that critics have viewed as being absorbed in radical-leftist political philosophy and rampant public corruption.

Noboa, initially elected in May of 2021 has also been criticized by opponents for favored business dealings and waging an ineffective war against the drug cartels and criminal organizations that have overwhelmed major Ecuadorian provinces, as well as the tremendously lucrative port cities of Durán and Guayaquil, where turf wars have erupted between rival gangs over control of the drug trade. Noboa was successful during his first few months in office with a tough campaign against crime in 2021. His approval ratings were then one of the highest in Latin America as he promised to clean up the nation’s streets and restore order in Ecuadorian society.

However, those numbers have since subsided due to growing insecurity of a resurgence in violence that has the nation and its residents on edge. Despite Noboa’s heavy-handed approach to the fight against crime, homicides in cities like Guayaquil have risen exponentially, tagging two killings per hour in the country’s port city, and seven kidnappings within that same timeframe.

Ecuador is situated within one of the most highly trafficked drug corridors in the entire world. The country shares a border with the southern provinces of Colombia, Putumayo and Nariño, the traditional strongholds of Colombia’s revolutionary guerrilla movement, the FARC.

The region is today in the middle of its own violent death throes between warring Colombian revolutionary factions like the 33rd Front, rebel dissidents of the now defunct FARC, and members of the ELN, or National Liberation Army, that have been fighting over territory to control the cultivation of illicit crops.

The southern regions of Colombia are also home to profitable drug routes that allow criminal gangs to push the distribution of narcotics north through greater Colombia, or further south into Ecuador.

Ecuador is also bordered with Peru to its south, another country that has witnessed a proliferation of coca cultivation and the distribution of cocaine north into Ecuador for future shipment from the coastal Guayaquil, a major transport hub where illicit narcotics are smuggled onto shipping containers by criminal groups, destined for the United States and Europe. The port city of Guayaquil is also part of a larger free trade agreement with the European Union that includes tariff liberalizations and the removal of regulatory or technical non-tariff barriers that inadvertently create incentives for criminal groups offering greater access to these ports used as major facilitators of the export of illicit drugs.

Ecuador’s criminal organizations and several other smaller gangs associated with Mexican drug cartels, as well as Balkan mafias with ties to Albania have taken advantage of the lax security arrangements after the presidency of Lenín Moreno from 2017 to 2021, who cut spending and peeled back on law enforcement resources, and freezing prison budgets as part of the implementation of austerity measures pressured by the International Monetary Fund.

This weakened security environment and the lack of border controls with top drug-producing neighbors of Peru and Colombia permitted the growth of violent criminal organizations to prosper in a region where the rise of violent criminal groups went largely unchecked.

In 2016, the disbandment of the FARC after a successful peace settlement was reached with the Colombia government also contributed to a sudden rise of smaller criminal factions in the region who were eager to fill the vacuum of a now inactive guerrilla group that once boasted of tens of thousands of combatants controlling most of Colombia’s southern rural regions for more than half a century.

But the problems of growing political divisiveness and domestic instability can also provide the Noboa government the opportunity to seek collaboration abroad, and to tackle the most urgent security threats posing mounting dangers at home. Noboa has opted to align himself politically with the new U.S. Trump administration, representing one of the few but staunchly pro-U.S. counterparts in Latin America. One other leader who has established himself with close ties to the U.S. president is Nayyib Bukele of the Central American republic of El Salvador.

An important piece of a U.S.-Ecuador partnership can revolve around the issue of crime and further enforcement of regional security in an effort to combat the distribution of drugs and the curtailment of the growing power and influence of transnational criminal organizations.

Such a partnership can resemble the one the U.S. administration has with El Salvador’s leader, and such arrangements are being worked out to put such an arrangement into practice. Noboa’s re-engagement against the gangs appears to be a prototype of Bukele’s crackdowns on the Salvadoran gangs of the early 2020s, such as MS-13 and Barrio 18, during the first years of his administration. Noboa has sought El Salvador’s council on the planned construction of an Ecuadorian mega-prison largely modeled on Bukele’s now highly controversial CECOT.

Noboa has also modeled a second campaign against the drug gangs on Bukele’s mano dura, or “iron fist” approach to law enforcement that has attracted the attention of critics, international human rights groups, and civil rights activists, as well as various Western governments accusing the president of skirting the nation’s constitution and abusing citizen’s civil liberties by enacting draconian and cruelly arbitrary emergency measures.

In January of 2024, the Noboa government declared a state of emergency in several of the nation’s departments by declaring an internal armed conflict against 22 criminal groups, bolstering security measures and intensifying operations that have led to an increase in violence, including “1,300 homicides in just the first fifty days of 2025”, according to Atlantic Council.

Noboa has also met with Erik Prince, founder and former CEO of Blackwater, an American private military group that made headlines internationally for an incident that involved the killing of civilians during the U.S.-led intervention into Iraq.

Prince recently touched down in Guayaquil to assess the security situation to provide aid and professional support to Ecuador’s security forces in combating the gangs and violent drug cartels operating in the region. On the security front, this could be an opportunity for Ecuador and the Noboa administration to exert its agency and play a more pivotal regional role against violent transnational crime networks. Ecuador is also open to the permanent positioning of the U.S. military to aid in the effort. Noboa’s opposition has denounced the plans.

The Noboa government is also looking at opportunities in trade and foreign investment. Ecuador does not have a free-trade agreement with the United States, unlike several other Latin American countries. This will expose the South American nation to the stated 10% tariff increase on existing goods, including non-tariff goods imposed by the U.S. Trump administration.

The port of Manta, which used to host a sizable U.S. airbase, is a significant seaport in western Ecuador, north of the city of Guayaquil, serving as a major hub for the country’s tuna industry and a crucial gateway for import and export activities. It has recently been floated for reopening to U.S. service members and can potentially play a part as leverage to negotiate reductions in tariffs on Ecuadorian exports. The U.S. airbase was shut down by Rafael Correa in 2009.

The Trump administration had campaigned on the winding down of American military involvement in far-flung corners of the world. But regaining a U.S. foothold in a strategically pivotal position in western Ecuador with oversight over tremendous sea traffic 1,100 kilometers from the Panama Canal will be a tempting rebuttal to recent Chinese inroads in America’s backyard.

Chinese investments and economic ties with Ecuador in recent years have also been an alarming trend to officials in Washington.

The two areas with which Ecuador and its people have struggled over most in recent years now appear to provide the reelected Noboa government new opportunities to capitalize on.

The restoration of order and economic growth with closer ties to the United States is what Noboa supporters campaigned on in the last election. It is a promise that Noboa made to his constituents. The lack of agency and investments to further advance the nation’s development is what has troubled Latin American nation-states since their inception. Ecuador is one of the newest among them with an opportunity to break the curse.