Although Washington’s heart had been in the right place, the application of an ambitious program like John F. Kennedy’s Alliance for Progress in a region like Latin America during the 1960s was destined for failure.

In a region where the disparities of class, rising wealth inequality, political corruption, abject poverty, daunting illiteracy rates, low wages, and extreme trade deficits — conditions for which such a program was undoubtedly designed to address — took priority over the more pertinent and long-standing political deformities that had been plaguing the region for at least a century before the announcement of Kennedy’s lofty vision. Political deformities that had allowed these economic and social straits to fester to begin with.

For the early 1900s, U.S. financial aid and investment towards the Latin Americans had been traditionally conditioned on the presence of friendly, U.S.-backed governments run by pro-American dictators who wouldn’t stir too much trouble for the vast, concomitant multinational interests that for decades relentlessly exploited these small, impoverished backwater republics.

Companies like United Fruit absorbed large swaths of Central American land, outsourcing its labor to hordes of desperate peasants, and monopolizing trade as American utility companies and railroad conglomerates owned all aspects of enterprising industries and public infrastructure of these nations, building close ties with local politicians, generals, and presidents, cutting costs and expanding operations whilst ensuring these interests were never challenged by populist native uprisings that were rapidly snuffed out by U.S.-funded Central American militaries and the endless supply of interventions led by U.S. Marines.

The poorest nations in the region, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala were prohibited from conducting trade with other foreign powers beyond that of Washington as the United States closed off the entire region as part of its Monroe Doctrine to consolidate U.S. hegemony over the Western Hemisphere, thereby relegating these southern republics to a state of total dependence on American imports.

These countries relied on U.S. goods so much that North American products made up as much as 90% of total imports of some states during much of the 20th century. Unsurprisingly, Central American exports didn’t fare much better. Endemic market fluctuations of raw materials like coffee, sugar, and cotton left Central American suppliers at the mercy of U.S. buyers who would ultimately set the price.

The combination of political, economic, and military supremacy over the Central American nation-states helped to foster an environment that was in dire need of an upgrade following the Second World War when the Soviet threat of communism was looking to capitalize on the mistreatment suffered by an abused and malnourished Latin American region beneath the pressing thumb of U.S. imperialism.

To counteract this threat, the Eisenhower administration during the 1950s became increasingly dependent on military leverage in the region to help bolster friendly regimes against the rising tide of Latin nationalism and anti-American discontent. But Eisenhower recognized the futility of armed intervention in Latin America. Lessons of the long and troubled history of the practice ran rampant in the back of the minds of advisors in Washington who were willing to learn from them.

Changes were required for the region, and men like Thomas Mann, advisor to Eisenhower and one of the most respectable experts of Latin American affairs in the 20th century, warned of the coming struggle of revolution, and that “events in the area threatened essential U.S. interests.”

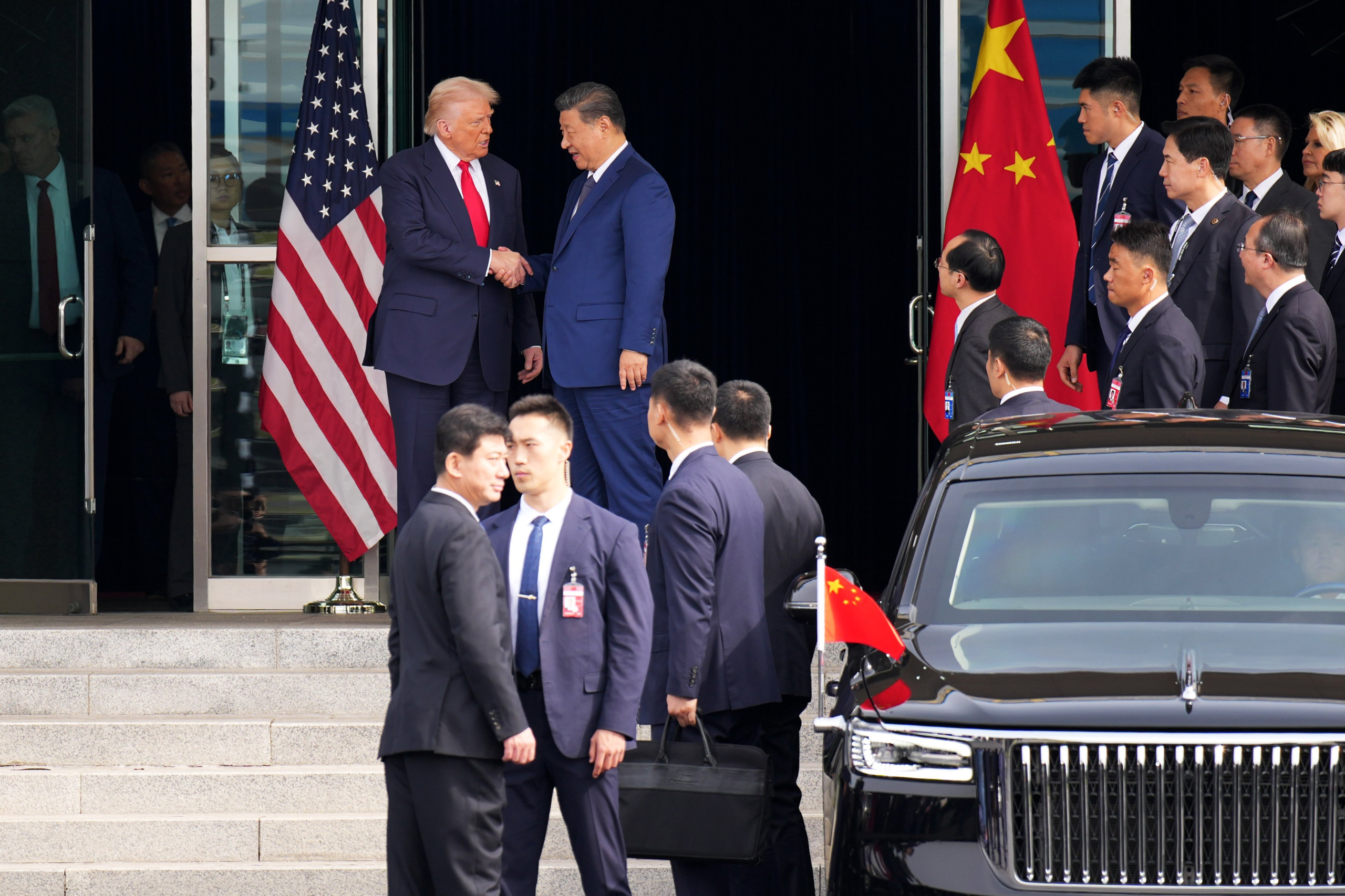

But Washington feared that too much change would unseat the coveted and now necessary power and strategic influence over the region in an era fraught with tension in the Cold War years of the 1960s.

So Washington, caught between a rock and hard place — a position that Americans had become so familiar with in Latin America, and a position that still rings true today — the dilemma between advancing efforts to achieve meaningful (and possibly revolutionary) sociopolitical transformation that could weaken U.S. political, economic and military influence or hang tough behind friendly tyrants to ensure such influence remains.

Change came indeed — or at least the attempt for it, a noble effort to depart from the troubled history of strong-arm U.S. foreign politics in Washington’s “backyard.”

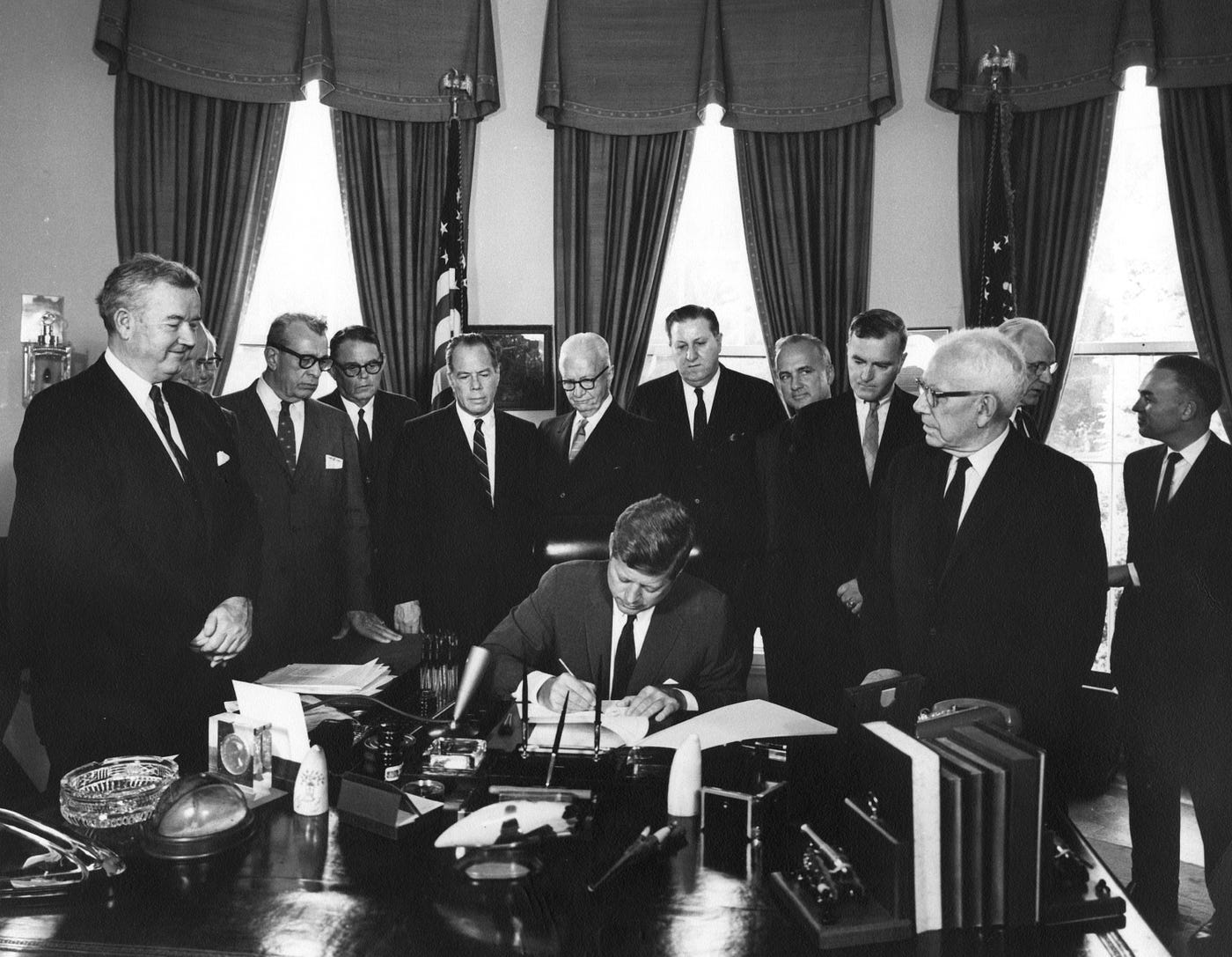

The change came in the form of the Kennedy administration, after his disaster of the Cuban Bay of Pigs in February of 1961, when Kennedy announced the launch of his Alliance for Progress program. The program was designed to initiate reforms to reduce the tragic social and economic disparities, and the disturbing state of poverty presided over by the Central American ruling class of wealthy landowning elites under the auspices of U.S. corporate interests and military intervention after more than half a century of corporate plunder.

The Alliance for Progress, a subsidiary with bureaucratic oversight by United States Aid and International Development (USAID) in Latin America, pledged a $20 billion investment in the region over the next 10 years in conjunction with private funding to help stimulate development in the region. Kennedy viewed the program as a “weapon to fight revolution in Latin America.”

The Castro takeover of Havana and the ouster of the Batista regime in 1959 left the Americans with a bruised eye. A Soviet stronghold 90 miles off the coast of Florida was bad enough, but what struck the U.S. government as even more alarming were the consequences of potentially more Latin American states “going the way of Cuba.” Kennedy announced, as part of his corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, that “another Cuba” will not be tolerated.

But the Alliance got off to a bad start. The economic improvements Washington projected were starkly overstated. The funds allocated to these Central American republics were poorly distributed, inevitably falling into the hands of corrupt oligarchs and parochial politicians and the U.S. multinational corporations “that controlled banks and mercantile businesses” operating throughout the region.

Problems began to mount when high birth rates clogged economic growth, overpopulation flooded into urban cities of nation-states that were already small enough. The small, weak, and poorly run governments could not manage this growth. Trade deficits also increased as wealthy landowners and farming oligarchs used USAID funds to reinvest into their own operations and diversify their exports away from traditional staple crops like grain and maize that were once the primary food source for a now overgrowing native population.

More investments filled the pockets of the rich, whilst scarcity in food products contributed to rising inflation, conversely, taking more money out of the pockets of the poor.

However, one area that was well supplied by comparison — an area to which USAID funds were very much indeed appropriately allocated — was military funding. U.S. military aid flooded these small economies of the Central American nation-states. Right about the time U.S. advisors began arriving in the Vietnamese lowlands, advisors began touching down in the Isthmus. “Hemispheric defense” and “internal security” became the overriding priority as the Alliance was failing to produce the economic results the Kennedy administration had hoped for.

Investments in military-grade equipment for Central American paramilitary forces were supplied to manage the growing violence and revolutionary unrest spreading like wildfire. Heavy weapons, helicopters, military-grade vehicles, and anti-riot equipment strengthened government forces, institutionalizing the brutally repressive, technically specialized, and highly trained U.S.-backed national police forces and military units that would eventually metamorphose into the notorious death squads of the 1980s Central American civil wars that slaughtered hundreds of thousands of people.

U.S. military intervention intensified during the Kennedy decade. The peaceful revolution that the region of Latin America so desperately needed had crumbled. The roadblocks to economic equality and the cutting away of the wealth disparities throughout Latin America were political in nature. The descendants of the strong and powerfully wealthy landowning elites of Central America were not going to simply give away their land cheaply, and the poor and disenfranchised proletariat were finished waiting patiently. The region was on a collision course between the haves and have-nots.

Between 1961 and 1966, the U.S. military had overthrown nine Latin American governments, including Guatemala and Honduras. Kennedy, and later Johnson during the mid-1960s refused to abandon the friendly dictators who helped keep the plates spinning. No one wanted to be the one to lose Latin America to the communist wave. But reluctant to give up efforts for serious transformation of the region’s economic situation, Washington had felt no other option available but to keep their hat in the ring by refusing to abandon their local strongmen for the sake of preserving national interests.

Thomas Mann argued against the Alliance program. Mann believed the Central American governments would go against any reforms that would in some way diminish their power or their wealth. Mann understood that the problems were political in nature. He understood that if the political mechanisms in Central America were not administered in such a way that would manage the flow of capital to its most effective use, then the contributions would be useless. In other words, “under the governmental systems in such areas as Central America, widespread, meaningful reform was impossible, no matter how much money was thrown at the program.”

One is forced to reconcile with the Kennedy naïveté. No doubt, Kennedy believed in the audacious vision of radically and peacefully transforming Latin America into a more equitable society, however betrayed by superfluous expectations. Mistakes and failures are much clearer in hindsight, but nevertheless, failure is so much more bitter when conceived by heroes.