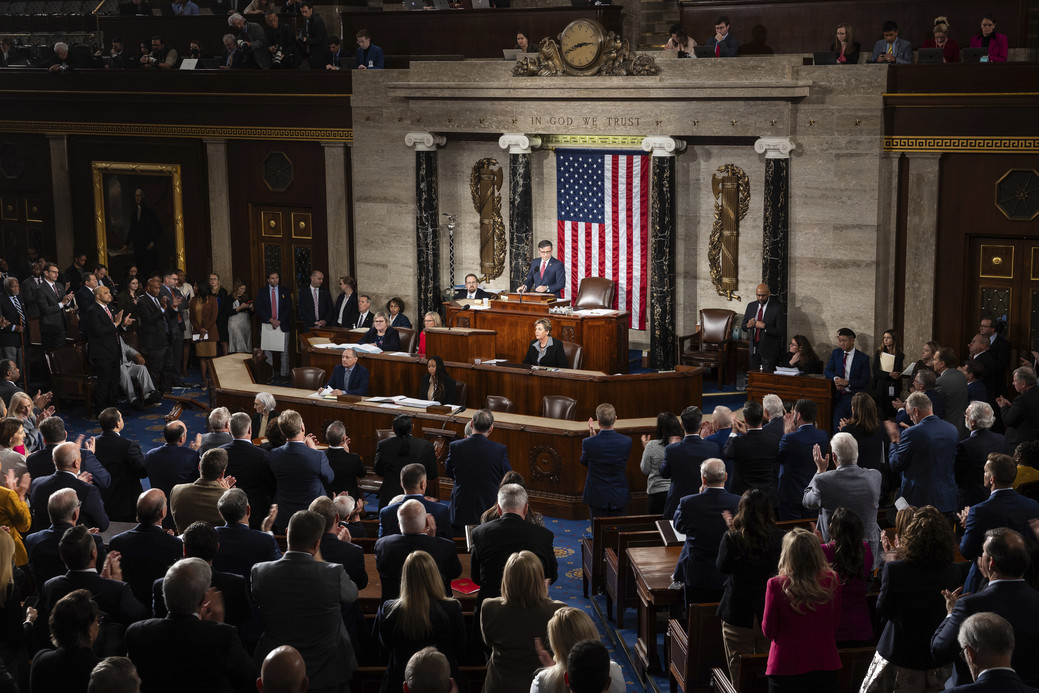

Since taking office, the new U.S. administration under Donald Trump and with the support of the Department of Homeland Security has taken a noticeably different course in the nation’s management of immigration policy across its southern border.

As of February 2025, according to numbers from Customs and Border Patrol (CBP), apprehensions of illegal crossings were at a record low of 8,347 between authorized ports of entry. This represents a “94% decrease from a year earlier when [the agency] apprehended over 140,000” illegal migrants.

This reduction of undocumented border crossings also indicates a decrease in the amount of migrant crime that comes with it. Crime that historically has left communities that are not only in close proximity to these high-traffic points of entry, susceptible to the violence, sexual predation, and illicit narcotics trafficking that is perpetrated by organized crime networks that took advantage of a largely unenforced and unchecked immigration system.

But the recent reduction in migration north originates even further south where migrants predominately from South America have transgressed through a dangerous jungle crossing that stretches across the lower provinces of Panama called the Darién Gap.

Crossings per week through the treacherous strip reached their lowest point since early 2020 at a mere 400 individuals. Weekly crossings through the gap reached as high as 30,000-35,000 during 2022 under the Biden administration.

This drop in crossings has the effect of dramatically diminishing a crucial source of revenue for prominent criminal organizations like the Gulf Clan who have a strong foothold throughout the area of northwest Colombia by monitoring lucrative smuggling routes for the facilitation of narcotics and human trafficking operations.

The removal of the U.S. Southern border as a viable destination for migrants to cross through has left them with few other options.

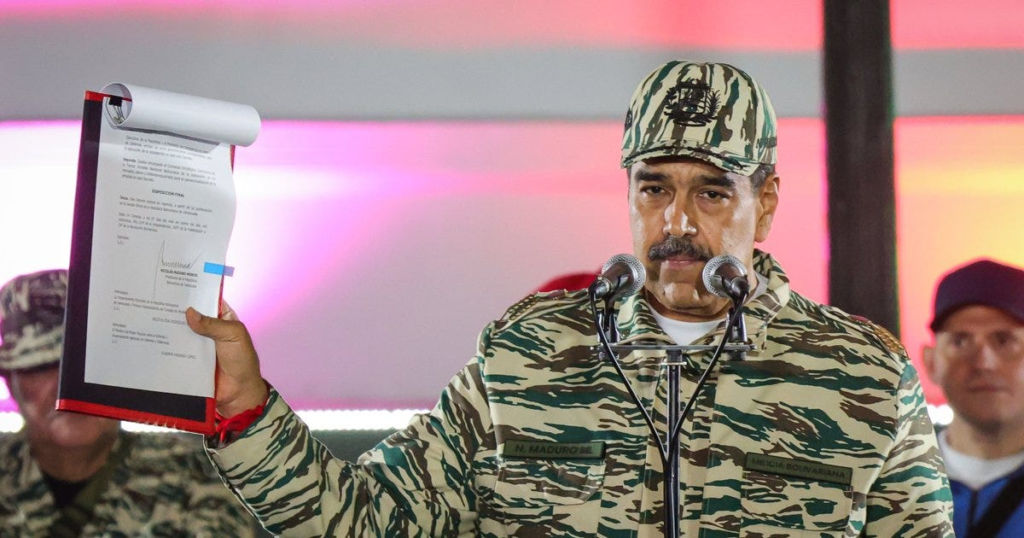

Since 2014, due to the rapid socio-economic deterioration in Venezuela for instance, eight million of its residents have sought refuge elsewhere. A report produced by Amnesty International in September of 2023 found that 70% of these eight million Venezuelan migrants relocated to Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Chile.

Colombia is currently host to the majority of this influx with nearly three million of them who now call the South American neighbor home.

In 2022, the newly elected President of Colombia, Gustavo Petro, a former rebel from the M-19 revolutionary group that gained popularity during the mid-1980s, sought to reestablish more cordial relations with the Maduro regime in Caracas and proposed closer collaboration with the Venezuelan government to ensure safer passage for migrants wanting to cross into Colombia. But relations between the two governments have since soured after Venezuela’s last election when Petro urged the Maduro government for more transparency in the face of resounding international accusations of fraud and abuse.

Venezuelans began pouring into Colombia more frequently in 2017, inspired by a more liberally-minded government and economic opportunities with access to medical treatment and public services that include employment assistance, education, temporary housing, and subsidized food.

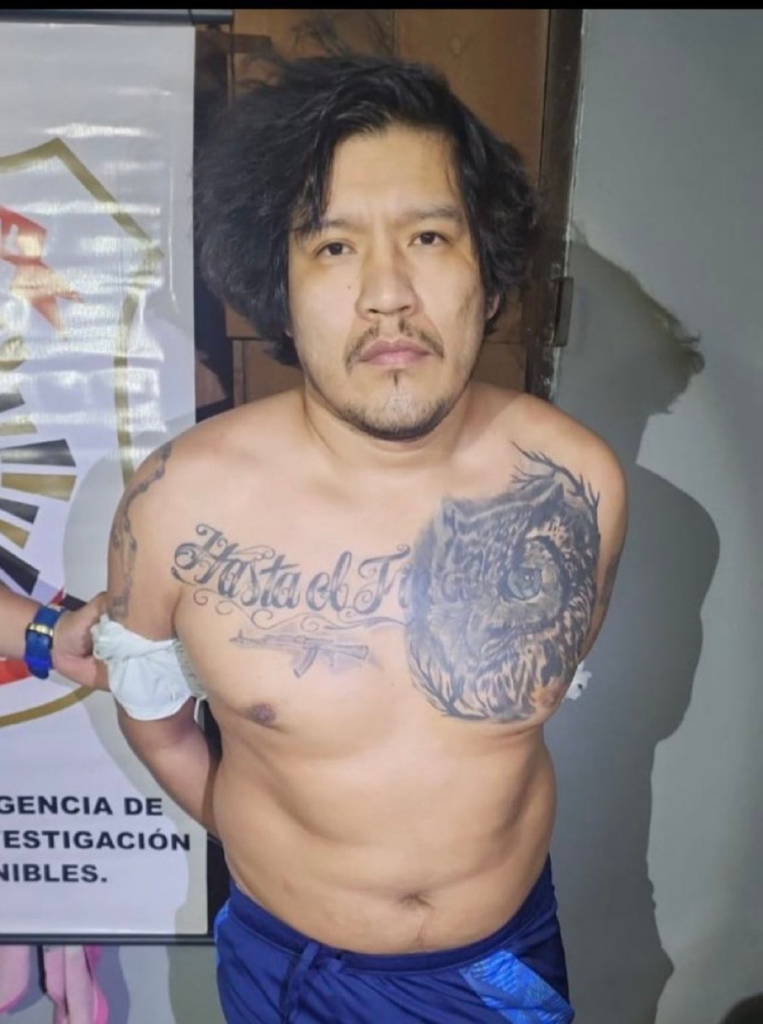

However, many migrants do not submit to the formal registration process and are often caught in the traps of organized crime groups who deliberately set out to recruit these “unregistered” migrants because of their unaccounted status with the Colombian state. Many more are recruited into armed guerrilla movements like the Ejército Popular de Liberación, ELP and the 33rd Front, a group of mainly FARC dissidents who have been warring with each other in a contest over coca territory and the highly lucrative drug routes throughout northern Colombia.

Venezuela shares a 2,200 km border with its Colombian neighbor. The northern portion of this area is made up of the rural and heavily forested hill regions of the provinces of Norte de Santander and Arauca on the Colombian side of the border, territory in great control of these various armed elements who profit from a human trafficking trade that has enjoyed a tremendous spur of business over the last few years.

Venezuela, a country ravaged by poverty, extreme desperation, public corruption, and ruthless crime has in many cases shaped the attitudes and modes of behavior of many of these migrants. Moreover, many of them, resulting from these negative habits, carry these behaviors with them when they make the journey westward. The desperation of these individuals will often compel them to take advantage of the high demand for additional members of these nefarious organizations.

Unfortunately, this has led to an increase in violent crime throughout these regions in northern Colombia. Their crimes include violent robberies, kidnapping, extortion, drug trafficking, and murder. These new trends have many local Colombians pointing out the harmful consequences of uncontrolled Venezuelan migration as they recognize that many of the delincuentes perpetrating these criminal activities are of Venezuelan origin, straining the patience of the native population.

The Colombians are a very understanding people, and tend to be very accommodating to the plights of others, as is the natural temperament of Latin Americans more generally. Many locals go to great lengths to stay mum to avoid coming across as either intolerant or unwelcoming. However, the local population of native Colombians, especially those of the northern regions have lived through their own plights, experiencing the struggle of a half-century of civil war and bloodshed from a violent guerrilla insurgency and unrestrained factional violence and turmoil between the central government, rebel groups, drug traffickers and paramilitary organizations all fighting for control over territory, cocaine, and political power.

During this same period, the rural peasant communities that tend to suffer most have described the central government as equally “intolerant” or “unwelcome” to the plights and concerns of the poor Colombian campesinos who are now to share what little else they have with others who bear no attachment to the land.

As the capacities of strained local resources are continually exhausted to satisfy the wants and needs of “outsiders” and at the expense of an already struggling local population in the rural regions, patience quickly becomes a scarce commodity. Frustration breeds resentment, and resentment breeds hatred. Internecine, local conflict is not unfamiliar throughout Colombia. The country has been engaged in them for decades. But the xenophobia towards Venezuelans can potentially add more fuel to an already burning fire with dangerous consequences for the “outsiders” and local populations alike. Affairs have the potential to turn deadly if the constant overflow of migrant traffic is not placated or sufficiently managed by the Colombian government and humanitarian agencies more suited to address the problem.

The urban city centers have also witnessed negative impacts from the steady influx of migratory trends into Colombia. The country retains, at times unabashedly one of the most robust informal economies throughout the entire region. Some estimates claim that 55% of its employed population work in the informal sector.

Employment services have been lack-lustered recently and unable to meet the volume of migrant needs for work due to tightened regulations following the COVID-19 pandemic, or more structural issues like slowing economic conditions being brought on by increasing inflation and unemployment. The physical evidence of this can be seen throughout the city of Bogotá.

On a recent visit, I noticed the presence of migrants sleeping in public parks or the national Plaza de Bolívar, or the selling of cheap goods in the surrounding city center. Local regulations and the enforcement of stricter measures to prohibit this loitering by police is part of a broader effort to drive many of these migrants away from the central administrative district of the capital, an area that many of them are drawn to because of the presence of high-income earners and foreign tourists.

Work and wages concerning Venezuelan migrants is also an area creating friction between “outsiders” versus locals. In October of 2022, Crisis Group found that roughly a quarter of the total Venezuelan migrants in Colombia were unemployed, pushing many to participate in more informal work like private rubbish collectors, street vendors, and cigarette sellers. It is also common for local and small enterprises to take advantage of the large supply of migrants by offering them work for miserable and extremely low wages. Migrants who take the work do so to the detriment of Colombian citizens whilst collectively lowering the median wages throughout small, medium, and large localities home to larger populations of Venezuelan migrants.

This will have the adverse effect of contributing to the growing feeling of xenophobic sentiments on the part of the native Colombian populations. But simultaneously, many more reject the opportunity of less but formal pay and would much rather prefer to earn their money through illicit means for the chance at more, adding to the antagonism towards an increasingly impatient local populace who are in the midst of a fight to combat crime in urban and rural communities. This is the proverbial catch-22 for the Venezuelan refugee.