It’s only been operational since February of 2023, but El Salvador’s flagship Terrorism Confinement Center – also known as CECOT – has already earned itself the notorious renown as Latin America’s most infamous mega-prison.

CECOT makes up a sprawling compound of 23 hectares fit to house 40,000 inmates and the now hunted members of Central America’s most ruthless gangs that only just a few years ago roamed the Salvadoran streets with absolute impunity – that at the height of the bloodshed, the gangs were responsible for 1,200 killings a month – ranking El Salvador in 2016 the murder capital of the world.

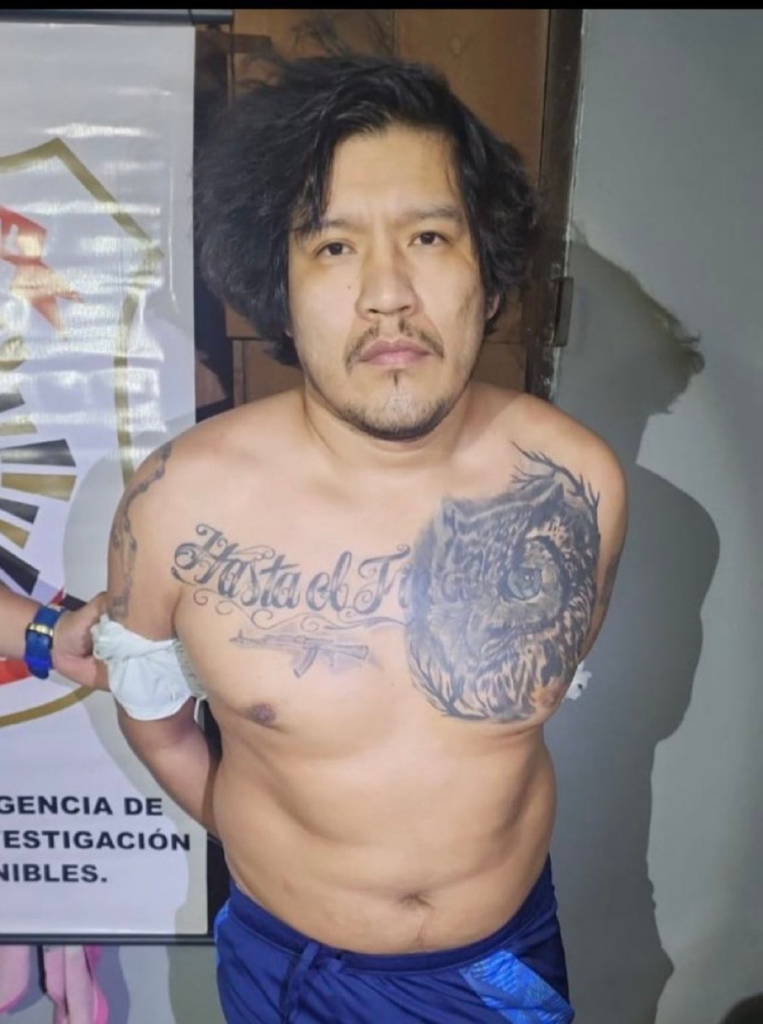

Members from Central America’s most violent street gangs like the Mara Salvatrucha 13, or MS-13, and the Barrios 18, or 18th Street gang make up most of the prisoners currently being held at CECOT after the administration of President Nayib Bukele announced new terrorist charges for individuals deemed members of these organizations when he issued the nation’s initial state of emergency in March of 2022 as part of his campaign to eradicate Salvadoran society of the criminal element.

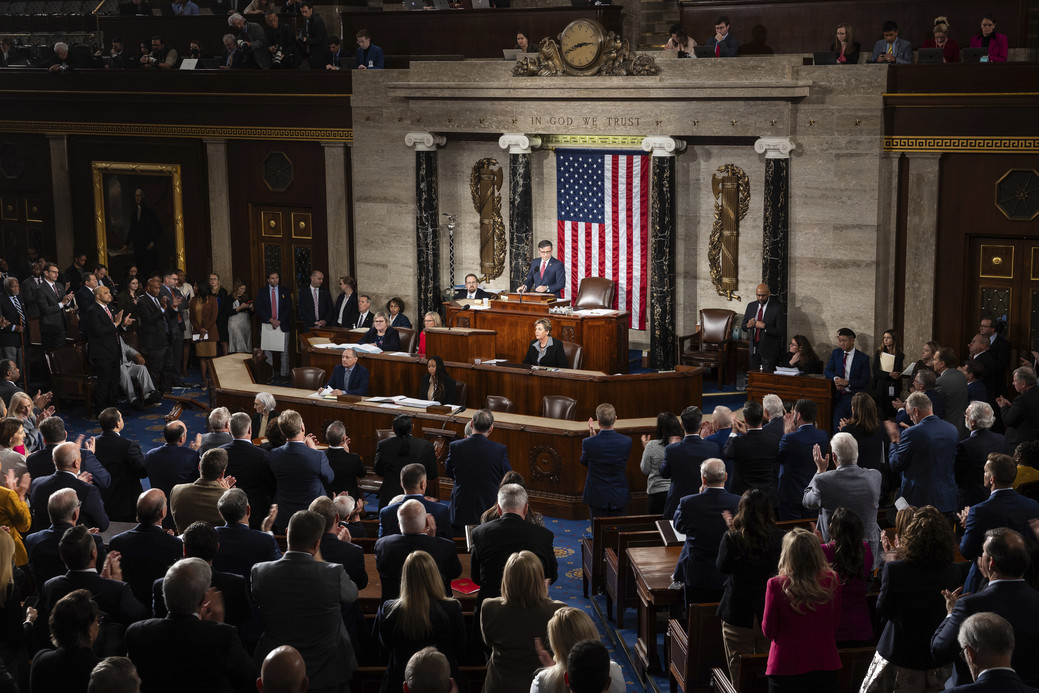

Since the Salvadoran congress granted Bukele extraordinary powers under the state of emergency declaration, and especially since CECOT has been admitting detainees deemed threats to the public, NGOs, civil liberty organizations and other international agencies have filed suits against the administration, accusing it of various human rights abuses and of violating civil liberties.

Bukele and his administration have also been on the receiving end of complaints launched by Western governments who have publicly criticized the Salvadoran government for its heavy-handed tactics and lack of due process.

However, over the past couple of weeks CECOT and the Bukele government have been the subject of widespread condemnation and international controversy in the aftermath of a flight that had transferred custody of 238 suspected members of the Venezuelan criminal organization, Tren de Aragua from the United States to Salvadoran authorities to be detained at CECOT as part of an agreement between the two governments.

The accord, which was negotiated in secrecy – would supply the Salvadoran government – with dozens of criminal migrants subject to deportation under U.S. law, and in return, the United States government would pay a fee of $6 million which equates to about $25,000 per head.

It wasn’t long before a firestorm of public rebuke from major media outlets throughout the world made headway, criticizing the move as a violation of due process and the demand for oversight and investigations, alleging the Trump administration of stripping the detainees of their civil liberties.

A U.S. federal judge immediately issued an injunction on the matter as the flight was in transit, which then commenced a legal battle that has now made its way up to the nation’s highest court.

But for Bukele, CECOT is more than a tool for negotiating fees to permanently house violent criminals to service the operating costs of the facility.

The compound and its functions are a tour de force. Optics matter in politics, and as CECOT is plastered across the chyrons of every major international news agency, the attention it garners will serve to further bolster the reputation of El Salvador as a committed member in the war on crime.

If one were to acknowledge the Salvadoran past, and how deeply its citizens were terrorized by these ruthless gangs, they would understand that the point is to instill fear in the minds of any potential criminality and the instability that accompanies it.

Public propaganda campaigns featuring the mega-prison should support this point. But so much more than this, CECOT is a symbol of a small, historically insignificant nation, and historical Central American client state specializing in coffee exports, now reborn, brimming with ambition and eager to stretch itself into becoming a more comprehensive player of regional influence in Latin America affairs.

Joseph S. Tulchin in his 2016 Latin America in International Politics discussed what he termed the exercise of agency, in which nations and leaders – even the most powerless – have the capacity for autonomous action, and to engage in the decision-making processes to further advance their interests within the international community. Tulchin reiterated the point by echoing Heraldo Muñoz, a Chilean political scientist that “No nation is without power and that the purpose of foreign policy is to make the most of the quota of power, soft or hard…” Tulchin believes that “Power should never be considered a zero-sum category in inter-American relations.”

The Salvadoran government is not merely accepting custody of foreign criminal migrants and shuffling them through its own justice system in a ploy to generate some extra cash. It is exercising its agency and utilizing a tool it has to further enhance its own international standing as a pioneer in the eradication of violent crime networks in a region that has become synonymous with the illicit flow of drugs, public corruption, and the tremendous power and control wielded by unrestrained criminal organizations.

The issue of “agency” has been a long-standing problem for Latin American nations, and a long-desired dream by their leaders who still today feel as if they have very little of it, only able to operate at the behest of the ever-growing shadow of U.S. hegemony.

To an extent, this has remained true. It was true at the turn of the 19th century when U.S. administrations were making it a habit of militarily intervening in the inter-local affairs of various republics. It was true before and after the Second World War. It was also true during the Cold War when the Monroe Doctrine was alive and well 150 years after its declaration. It has also recently been the case since the start of the Global War on Terror when national security interests took superiority over Latin American autonomy.

Over the last 40 years the countries of the Isthmus, and of the northern Andes, primarily Colombia have been reeling from their own domestic issues.

Historically, Latin American nations have struggled to drive towards autonomy in their own decision-making processes in regional affairs because of internal social instability like plights of public corruption, the rampant drug trade of the 1980s and 1990s, the armed guerrilla movements, i.e. the FARC, regional border disputes between Chile, Bolivia, Peru, Paraguay and others, as well as the spread of violent crime and a gang epidemic that overwhelmed the weak central state and the absence of rule of law in El Salvador.

The most successful nations in the region have managed to clamp down on violent crime, restrict the illicit drug flow, and reduce public corruption and inflation whilst institutionalizing the rule of law with a police force, municipal or national, that can be reined in with total oversight by the central government and insusceptible to abuse.

El Salvador is a demonstration of this, by utilizing CECOT to establish collaborative efforts with other governments to pursue the overarching vision of regional stability.

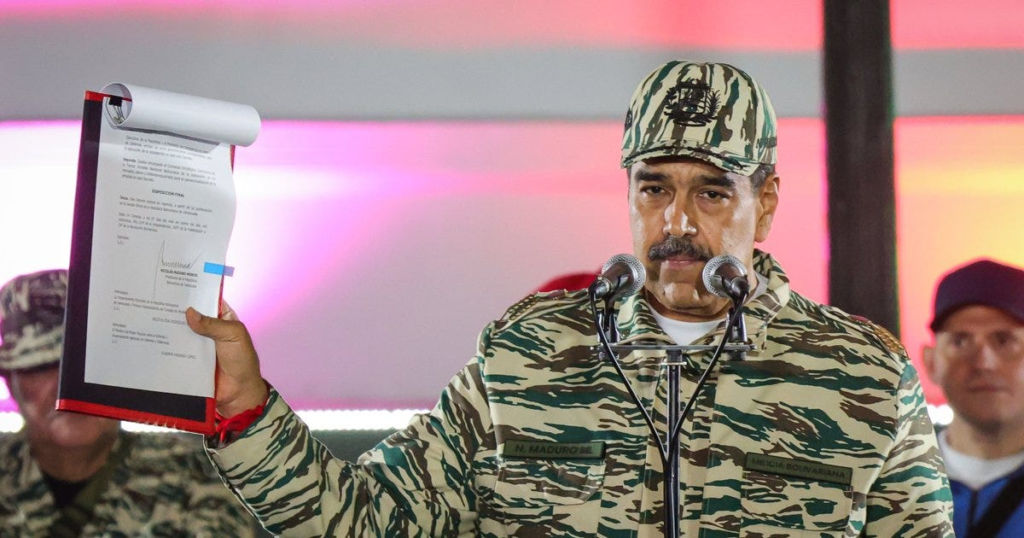

After the recent reelection of Nicolás Maduro of Venezuela in July of last year where international agencies have reported widespread fraud, Nayib Bukele was one of the first national leaders to condemn the election and refuse to acknowledge Maduro as the legitimate president of Venezuela.

Bukele has also publicly criticized the authoritarian leadership of Maduro whilst publicly supporting demonstrations in Caracas against the Venezuelan government. This has the effect of bolstering his own standing within the international community, especially in Latin America as a leader among Central American nations that have historically had a poor track record in democratic principles.

Bukele has recently partnered with Ecuador, which is experiencing its own violent crime epidemic as rival street gangs battle over territory to control the drug routes from Peru and further north. Ecuador, which now has a murder rate of 47 per 100,000 is the deadliest nation in all the western hemisphere.

The current president of Ecuador, Daniel Noboa, inspired by CECOT, plans to build his own terrorist confinement center with the help of Salvadoran advisors, whilst simultaneously adopting the Salvadoran model of crime enforcement to rid the South American nation of its criminal elements.

In August of 2024, President Bukele had also arranged a meeting with Erik Prince, founder and former CEO of private security firm, Blackwater. The meeting revolved around a variety of topics from combating crime to the overall regional security situation throughout Latin America.

During the meeting, Bukele stressed to Prince, who has close relationships with several members of the U.S. Trump administration, how significant it would be for the U.S. State Department to downgrade the Central American country’s travel advisory status from its current Level 3.

In February of the following year, the Trump administration downgraded the country to Level 2 status, which would have the ultimate effect of encouraging tourism and foreign investment, further improving the nation’s economy.

Last month, Daniel Noboa of Ecuador also met with Prince to discuss similar topics. It is planned that a contingent of security advisors working with Prince will be arriving in Ecuador to begin coordinating efforts to combat the criminal gangs, alongside Ecuadorian military and security forces.

Now in conjunction with the U.S. Trump administration and supporting their efforts to eliminate the crime wave, and remove violent migrants from the United States who are considered threats to public safety, the Bukele government is attempting to demonstrate to the international community that El Salvador is a serious player who is willing to collaborate with the most powerful nation in the world in its effort to contribute to regional stability throughout Latin America.

How El Salvador continues to utilize CECOT and its state security institutions to further advance its interests still remains to be seen. But the president of the Central American republic undoubtedly has a broader vision for his country, and for the role he would like to see it fulfill in the coming years.

For now, CECOT will be used as a cudgel by liberal politicians to demonstrate what they claim are the extreme, punitive, or dictatorial measures that El Salvador is employing in usurping the rights and civil liberties of suspected criminals.

CECOT will also be used as a shining beacon by conservative politicians in Latin America and the U.S. for its effectiveness in removing violent criminals from their nation’s streets, and a symbol to convey power and fear in the hearts of local criminal elements.

For El Salvador in particular, it will continue to be used as a tool by the Salvadoran government to exercise its agency in pursuit of broader influence in inter-American affairs.